This is the transcript of a talk I gave at the 2020 Play Festival. The festival normally takes place in Hamburg but was moved online due to COVID. It’s a sequel to my previous Indiepocalypse talk. The Google Slides can be found here , a pixelated video recording is here.

Today I’m gonna talk about games without players. And not just as a thought experiment, but as material necessity As a possible way to deal with the contradictions of the attention economy.

In the last decade we have witnessed a democratization of the means of production of videogames.

Anybody can make games thanks to tools, communities, attitudes. And thanks to the opening of digital distribution channels.

The most successful companies today don’t make money by selling content, services or commodities but by distributing it, by controlling their marketplaces. When we democratize the means of production and distribution we should expect a proliferation of cultural producers and cultural products.

More recently people have been to talking about the Indiepocalypse in games.

A phenomenon related to:

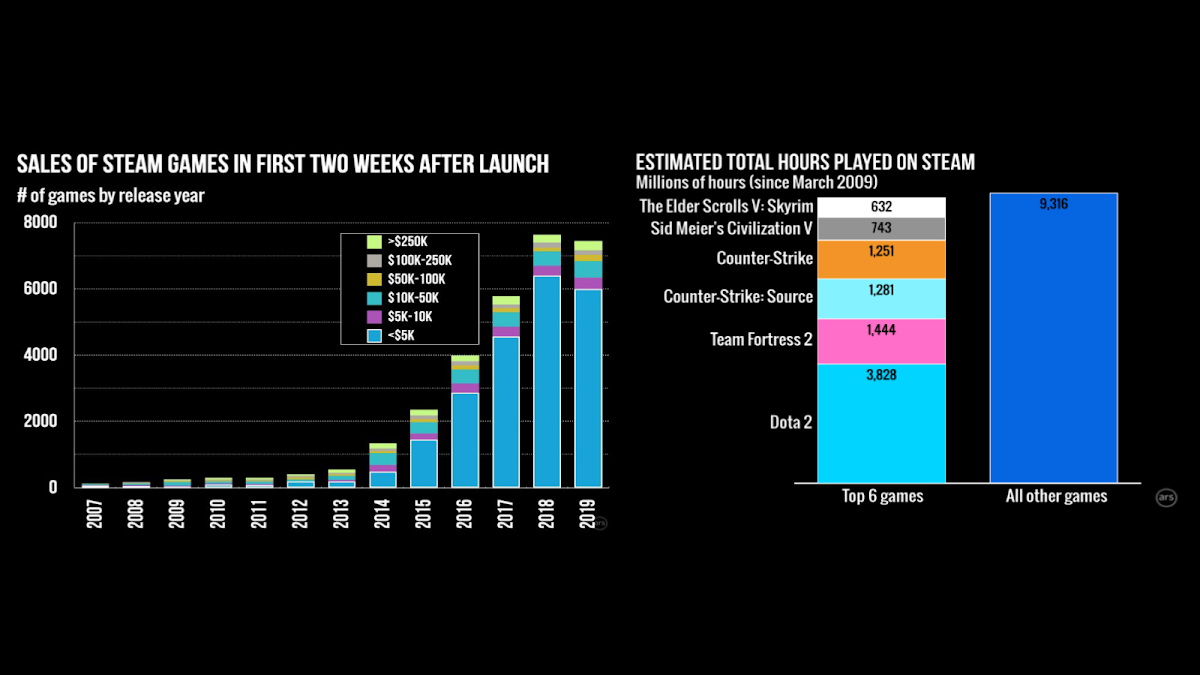

*The seemingly exponential increase in the number of releases.

*The decreasing sales and revenues, even when take into account quality and reviews.

*A winner take all distribution of sales and time.

These are trends that threaten the commercial sustainability of independent game making

We can argue about the statistics, we can argue whether having “too many games” is good or bad, but regardless I believe there is a inherent tension and a crisis of overproduction.

Because games need to be played. Playing takes time. And our time, our attention, is a scarce resource. A resource that is contended by many industries, Social media, online television, our employers and so on…

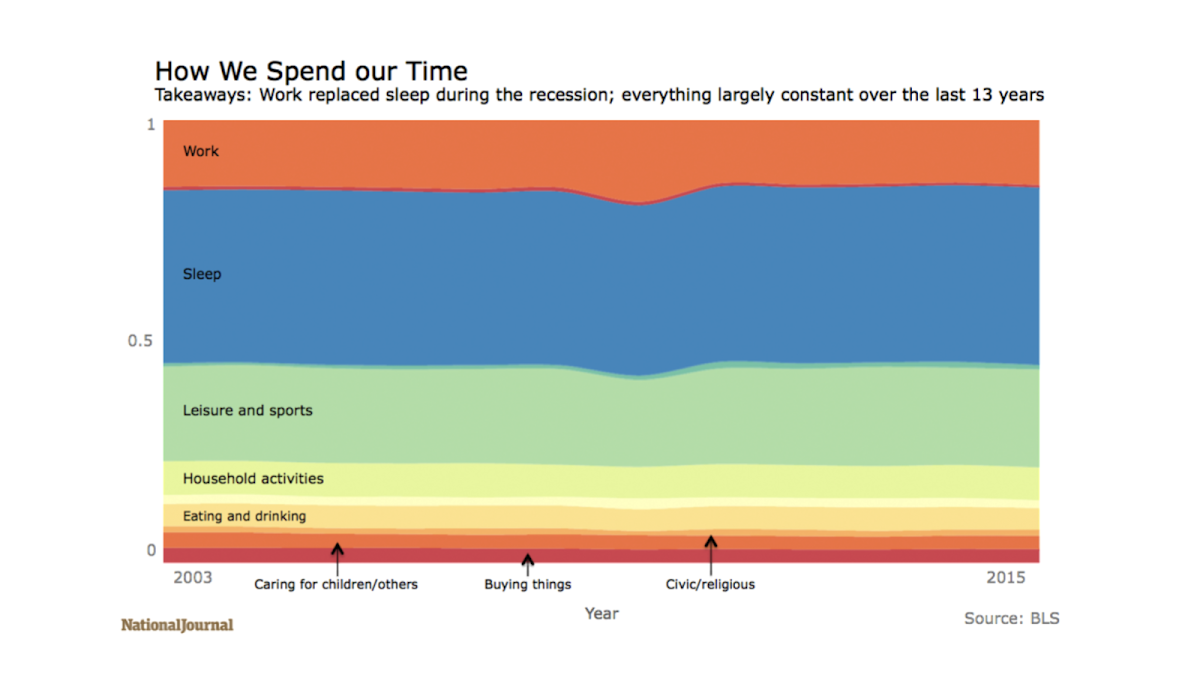

The amount of free time we have, and the way we spend it didn’t change much in the last 15 years. At least in the US (where it’s regularly tracked).

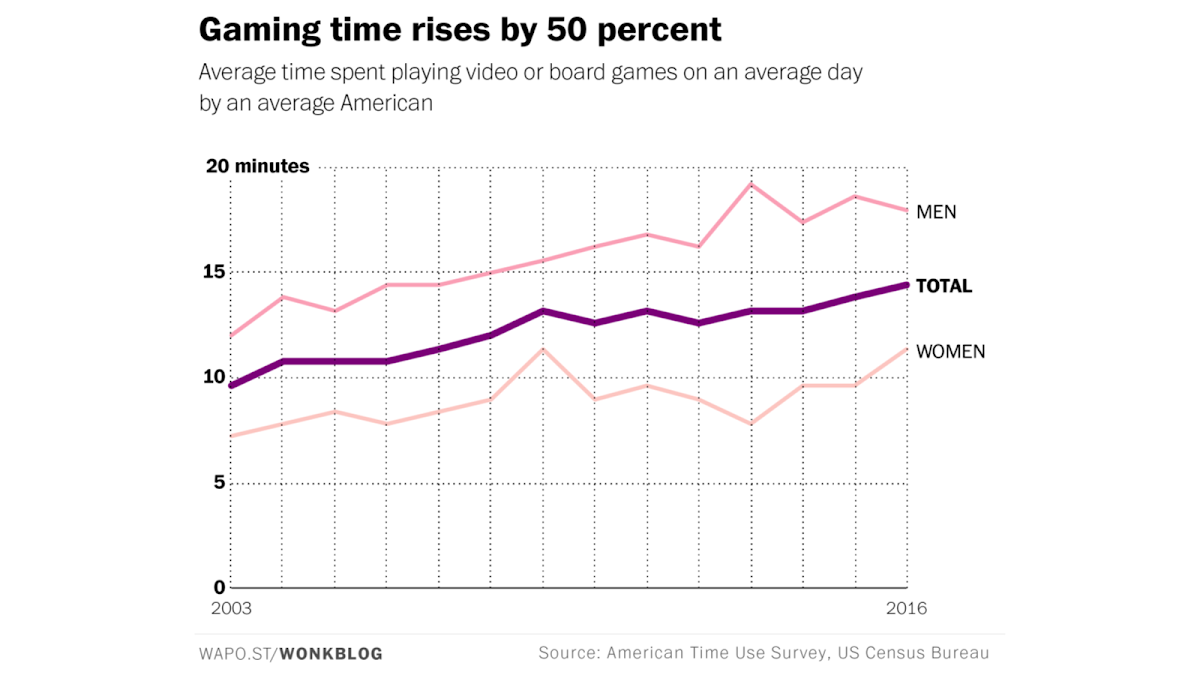

The time spent playing games did increase, but not by much.

A couple of years ago I gave a talk about possible and impossible ways to continue making games in this crisis of attention (you can find it online) Some solutions I outlined were:

Finding new audiences Human and non human.

Demanding more free time.

Making games that colonize new spaces and context in our lives.

Decommodifying games. Funding culturally valuable games as a public goods, so they don’t need to find large paying audiences.

But there’s another approach that involves rethinking not only what games are but also what their place and purpose in our lives is.

It’s the idea of games without players. Or the idea of partially, gradually, decoupling games from an extremely competitive attention economy.

This process is already happening organically with esports, and youtube streamers.

You don’t have to be a committed player to be part of the gaming community. Millions of people consume games passively.

And you can do that while doing other things: maybe the stream is on another tab or another screen.

Game spectatorship fits our fragmented attention better than being totally immersed in a game.

Another early indicator was the popularity of Farmville and many social games that kind of run in the background.

Like Neko Atsune, which is a virtual pet collecting game. You have to check now and then, it’s more of a pleasant compulsion than a game in the traditional sense.

Farmville may not be as popular anymore but many top selling games on mobile are clicker games Also known as idle games or incremental games. In games like Cookie Clicker you can progress with little action, you can keep them running at work, or while you are playing other games.

Clicker games started as a parody of Farmville. Cow Clicker was a minimalist distillation of the addicting Facebook games circa 2010. But people got really into it.

Universal Paperclips, a more recent hit in the genre, is also ironic and… self-aware. But most of idle games are not really jokes, and they are not satirical.

The most notable precursor of idle games was Progress Quest which satirized leveling and grinding in RPG games. It doesn’t even require clicks. You just run it and it plays itself. Your hero kills monsters, collects loot, levels up.

It’s a zero player game or a self playing game.

Self playing games have always been quite popular in the art world.

If you want to put a game in a museum, if you want to make art with games or game engines, it helps if they are not interactive.

A game that plays itself looks clever, subversive. The artist mods or breaks a commercial game in a purposeful way creating an enigmatic object that is in dialogue with generative art. And besides, a lot of people are not comfortable with interacting with computers in a museum anyway.

DeResFX.Kill(KarmaPhysics < Elvis) by Brody Condon (2004)

A radical Unreal Tournament mod (before Unreal was an engine)

This collection of hacked bowling games play themselves in perpetuity. They use sophisticated controller hacks. Maybe it’s a reference to the famous book Bowling Alone about the decline of American communities.

And you know, it’s a really cool installation to watch, it mirrors a bowling lane with its life-size projections. It’s a history of bowling games representations across different consoles. It makes you think about the evolution of interfaces and graphics, how different designers approached the same “problems”…

If idle games rely on scheduled rewards and an abstract sense of progress. Artistic self-playing games aim to produce an aesthetic effect. They are compelling because they are unpredictable and rich even without human intervention.

This is a Quake Mod that creates music and glitch visual from a battle between the bots. The bots are kind of struggling in this unfamiliar low gravity world.

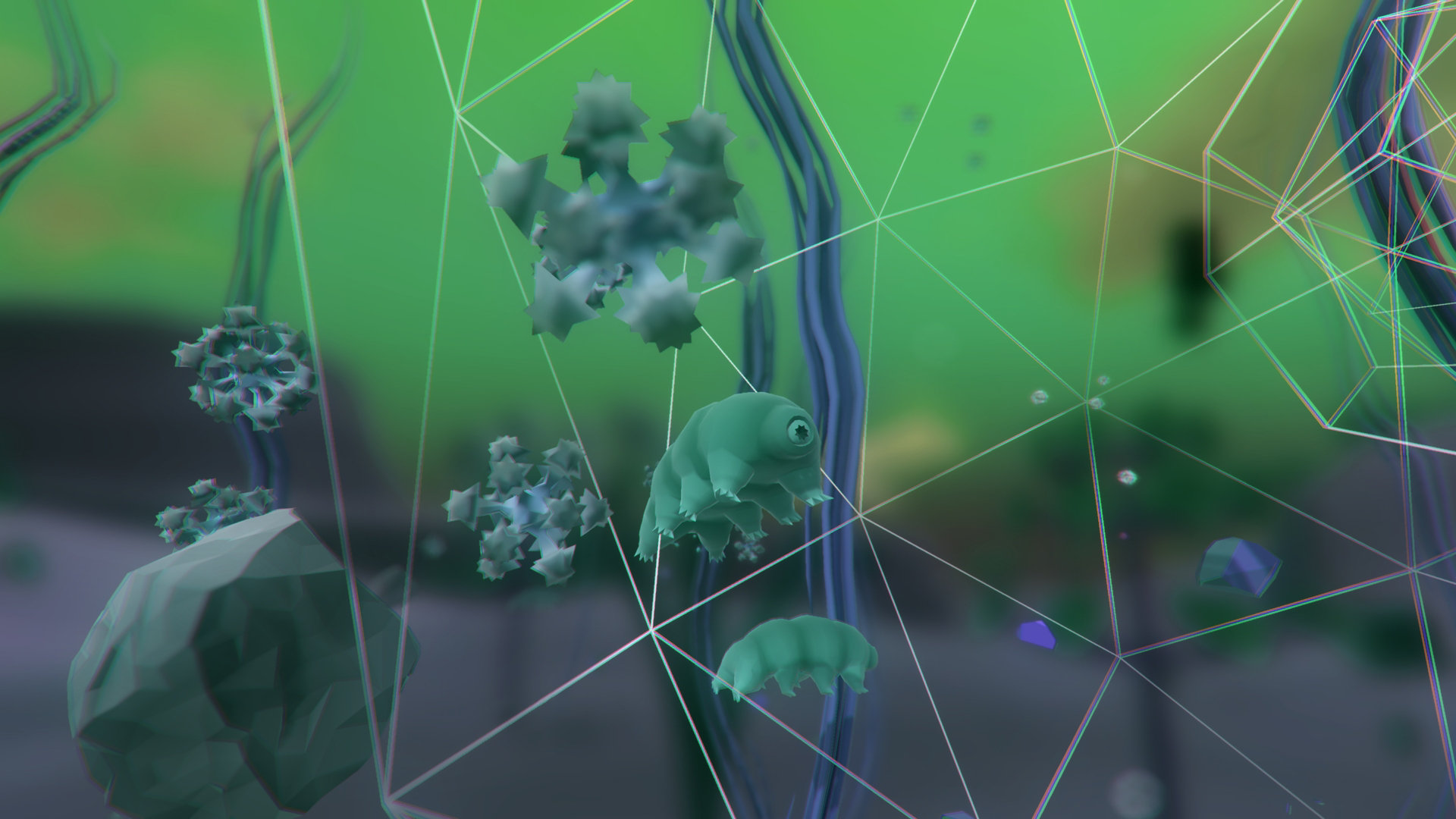

This is Emissary, a trilogy of self playing games by Ian Cheng. They are agent based simulations, they have characters and they look very much like indie games. They also have a rich lore and a consistent world.

They are museum pieces: you sit and watch them running, wondering about the relationships between these creatures, their strange rituals and habits.

Some self playing games found a market outside of the art world. David OReilly Mountain is a popular one. It shows a mountain and its thoughts. Objects randomly crash and accumulate over a long period of time. It’s an existential virtual pet

Mountain’s follow up Everything, is even more interesting because while it’s played in a rather traditional way with a controller, it also has a self-playing mode that kicks in automatically when you are not interacting with it. It seamlessly moves from one player to zero player. From game to screen saver. And this is very consistent with the game’s philosophy which is all about decentering the human perspective. You are not the hero, You are just a node in an interconnected world. A world that seems to exists before you, and continues to exists after you stop playing.

In Abzu the self playing areas are unlockable features. They turn the exploration game into a kind of relaxing screen saver. It makes me wonder if games can occupy the space of fish tanks. The fish tanks is somewhere between a pet and a piece furniture.

Dreeps is a richly illustrated zero player games. It plays like an rpg: it’s a kind of graphical Progress Quest.

Two interesting things about Dreeps: it’s probably the only self playing game that directly addresses the attention economy. It’s pitched as game for people with no time.

It also tries to avoid the compulsion loop. It’s subtitled “alarm playing game”, because you can set an alarm to check the progress. It’s an efficient background game that really respects your time.

Some self playing games derive from traditional games And just replace human players with bots Meaning the the AI that is built in the game. One artistic example is the musical Quake mod I showed before.

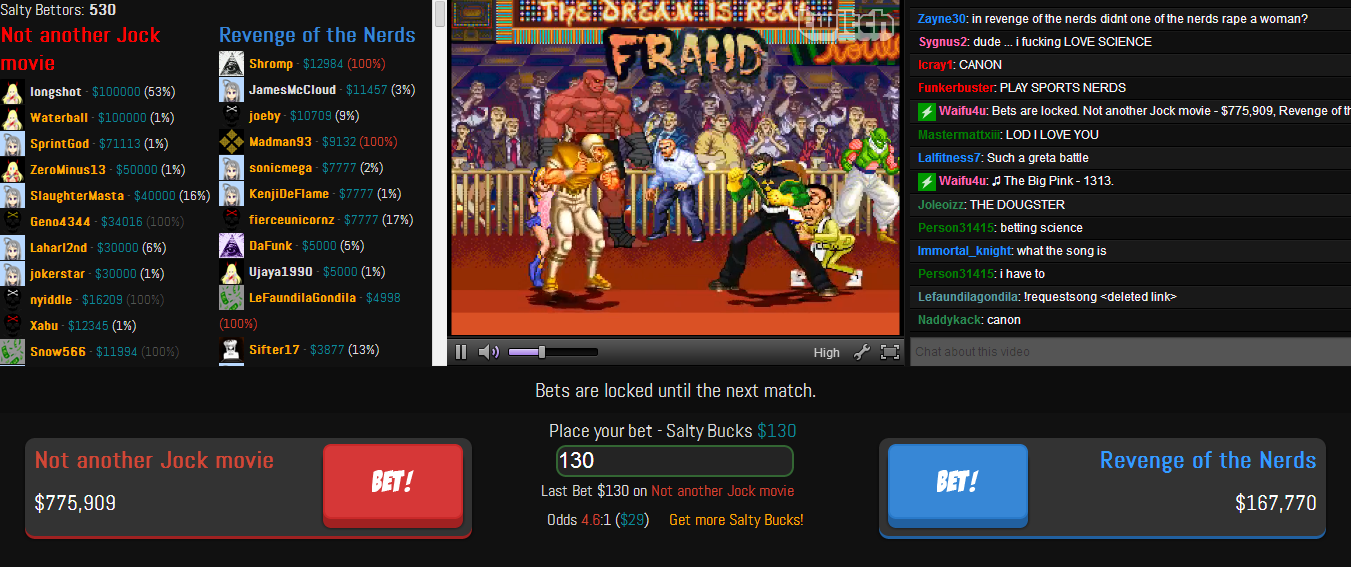

Another popular one is Salty Bet It’s a continuously streamed series of matches on the fighting game engine MUGEN Which includes hundreds of characters ripped from commercial games or created by the community The game is entirely played by the AI And the human players just spectate and bet fake money

And what about the Autochess or auto battle genre? It started as a mod of DOTA and it became its own esport. Players set up their team of creatures in a chessboard like arena and watch them fighting. It does require attention and interaction, but it’s just in the set up phase, it is mostly a self-playing game.

This is a neural network learning to play mario It it’s not a bot in that it’s not programmed to behave like a human It just knows the state of the game, the inputs and parameter of success It start pressing buttons at random and over time it learns to avoid obstacles and enemies. This is field of research in AI, or better, Machine Learning Not different from AI playing Chess or GO Automating play is a fun problem to solve if you are a programmer And I wonder if it can become a higher level of play

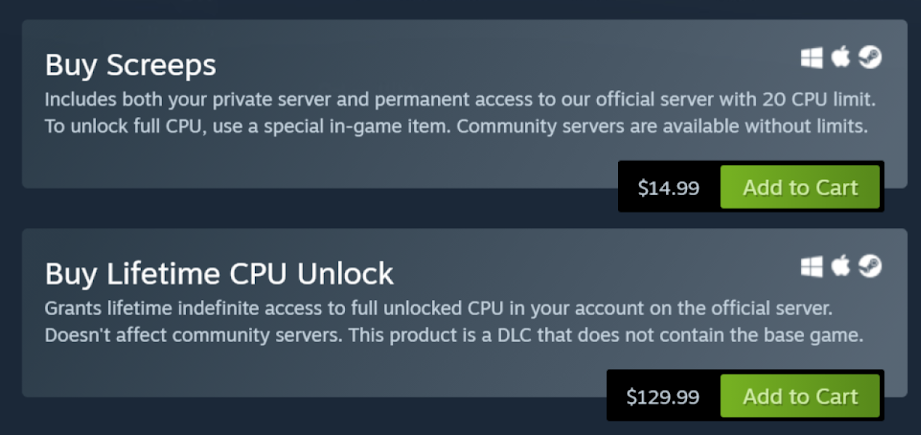

AI played games are related to programming and bot games Like Core War or gladiatorbots Screeps is a competitive real time strategy game in which you program the behavior of your unit And let your AI fight against other people AI unsupervised, While you are sleeping, or working

I like how Screeps has its own business model, because the AIs have to run continuously on the cloud.

Somebody has to pay for nobody to play.

There are other competitive games in which you program AI or autonomous agents: Gladiatorbots, or the assembly game Core War from 1984. Or even Conway’s Game of life, which is a cellular automata, a sandbox simulation that you set up and let run. It’s not quite a game but people can design/discover emergent combinations and share their patterns.

AI and bot programming games are a niche genre because coding is still a specialized skill. To me they feel more work than play.

But I can see this genre crossing over with single-player programming games like Fantastic Contraption, 7 Billion Humans, Factorio, or many Zachatronics games, or this one still in development called Crescent Loom. All these games figured out intuitive, playful ways to program behaviors.

I think we still haven’t had the breakthrough title in this category, the Minecraft, or DOTA hit that popularizes a niche genre.

San Andreas Deer cam is both an artistic mod, a bot game, and a self playing game. It’s a mod of GTA V that replaces the main character with the NPC deer from the game.

It was left streaming on twitch for months and gained a big following. It provided plenty of entertainment because GTA V is huge and very emergent. It’s also a meaningful piece. The deer is nature’s trickster causing mayhem and slapstick comedy in the humans’ world. It brings attention to a game world that is all about cars and crimes. It’s poetic and tragic. And because it was a long event that enabled word of mouth, it created its own community of spectators, with its own memes and lore. Which brings me to another point…

Streaming, speedrunning, and esports showed us that games can produce communities and cultures around games, and without the necessity of play. But they are often a byproduct, something that happens organically around a popular game. So my question is: can you design games or situations meant to be primarily experienced as a community?

Twitch Plays Pokemon turns the single player gameboy game into a massively multiplayer experience. Thousands of players can go on Twitch and type commands in the chat, controlling a single game running on the streamers’ machine. The result is this absurd, schizophrenic experience. It went on for months, they introduced more structured voting systems and eventually they Twitch players beat the game. Twitch Plays Pokemon is a game without players in a way because there are so many players over a long shared session, that the individual agency is diluted to almost nothing.

But the shared experience, this long difficult journey, produced its own fandom, its own lore and memes. A game can produce shared meaning even if its not played, as long as it gives you something to talk about.

And that’s also how traditional sports function.

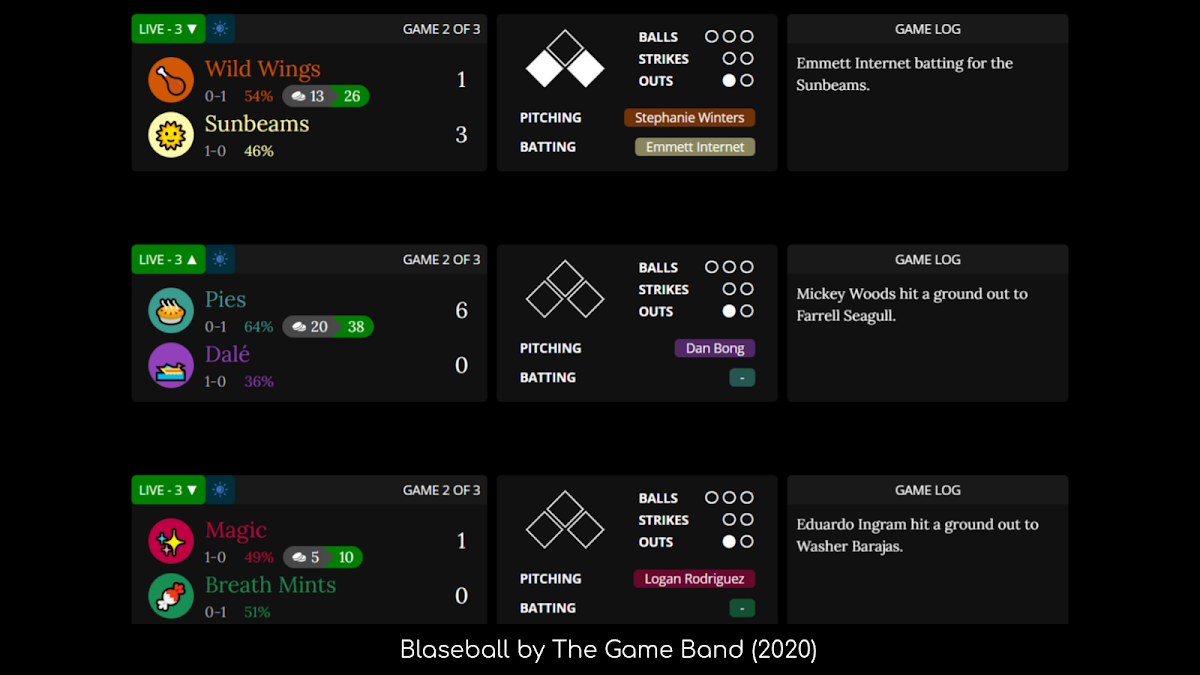

Blaseball, which came out this year, may be the first indie game that intentionally tries to create its own culture and vernacular. It’s basically a fantasy baseball game in which you gain currency by betting on automated games, rendered through a series of text events. Each team and player has their own stats, so you can try to make educated guesses.

But Blaseball is much more than that. There is a metagame in which players can modify the rules. It has an evolving story, and new surreal events and mechanics are added in response to the community. I think the creators call it improvisational game development, a “yes and…” exchange between creators and players.

There is a sprawling wiki narrating the seasons, a lot of fan art, and a discord in which players exchange opinions and theories. It’s very inside-jokey, and I personally don’t like it for the same reasons I don’t like sports talk. But I think we’ll see more experiments like this in the future. Because they provide meaning and sense of belonging with a limited investment of attention.

Here’s another leap: most of the games right now, most of the games ever made, are games without players. Games that don’t find an audience. Games that are left unplayed in your steam library. Unreleased games.

I made quite a lot of games that almost nobody played. It’s fine, I’m an artist, I don’t care.

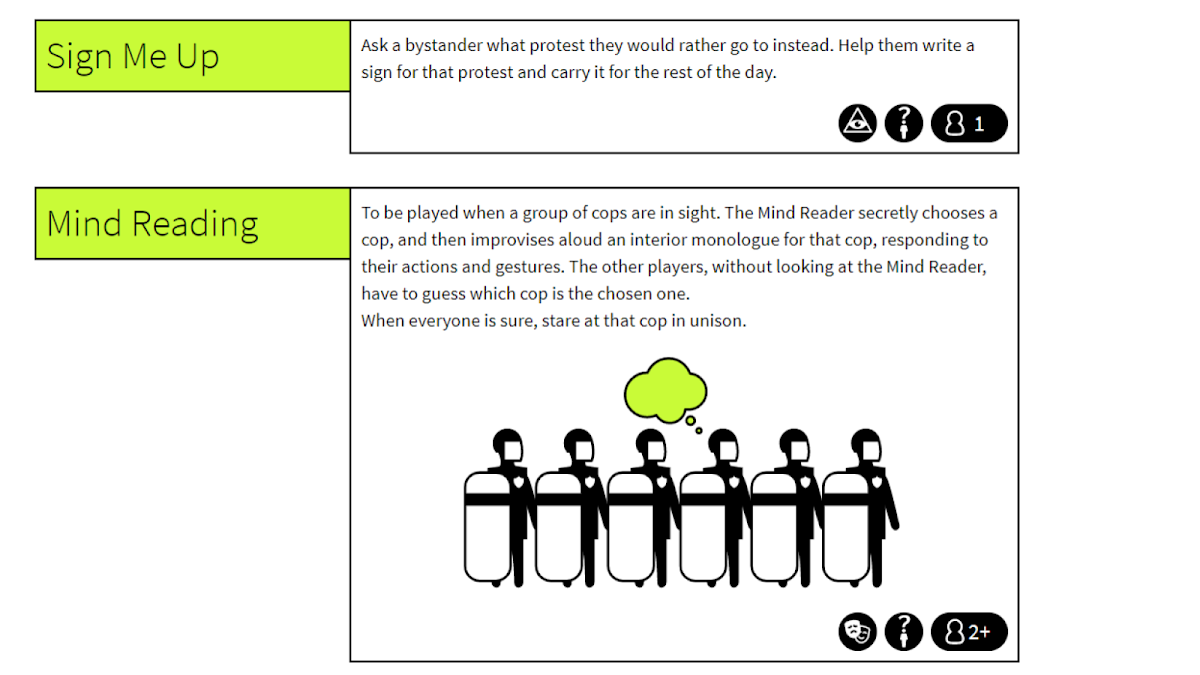

But there are two projects that were designed with this aspect in. One is casual games for Protesters, a collaboration between me, and poet and performer Harry Giles. It’s a collection of non digital games to be played during marches, rallies, demonstrations.

All of them have been actually tested, and “work” as games. But some of them were more like poems, or they were asking a lot from players in terms of risk and committment.

Casual Games for Protesters has been appreciated a lot as a concept. But the games were never really put into practice in the context we imagined it. I don’t think many people actually played these games outside of workshops. And this is for a variety of reasons I don’t have time to talk about.

But that’s fine. Because to me the project was more of a provocation, a speculative object. What if we used games to enrich existing movements as opposed to educate or “raise awareness”? What if games were employed to make activism less formulaic and more engaging? That vision is still there, whether you play these games or you just read the instructions and imagine these games being played.

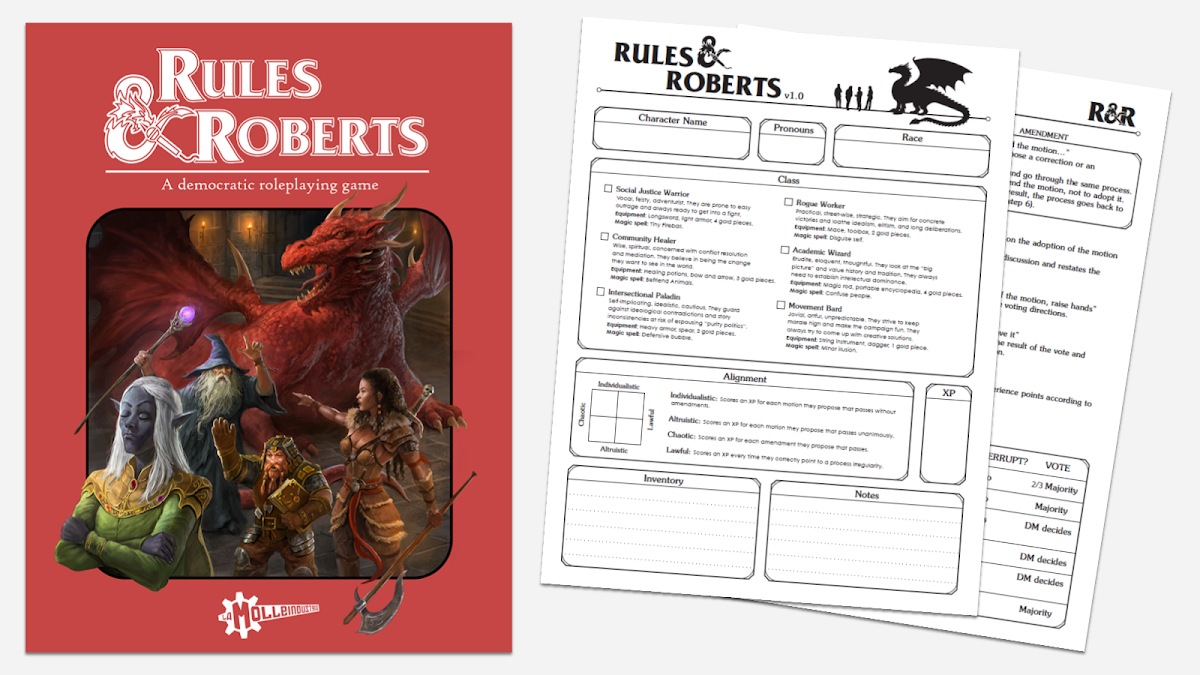

My latest game Rules and Roberts is a simplified D&D meant to teach a set of parliamentary procedures called Robert’s Rules of Order. The are rules used by many associations in the United States. Basically instead of declaring your actions or discussing the next moves informally, every action has to be discussed using this highly structured process.

It’s kind of absurd and pretty awful to play, but it’s a functioning game that actually familiarizes people with these procedures. More than four thousand people downloaded, many even paid for it, but I’m sure not many of them actually played it. But it’s ok, because it can still make a point. It can be a fun or cursed artifact to think about.

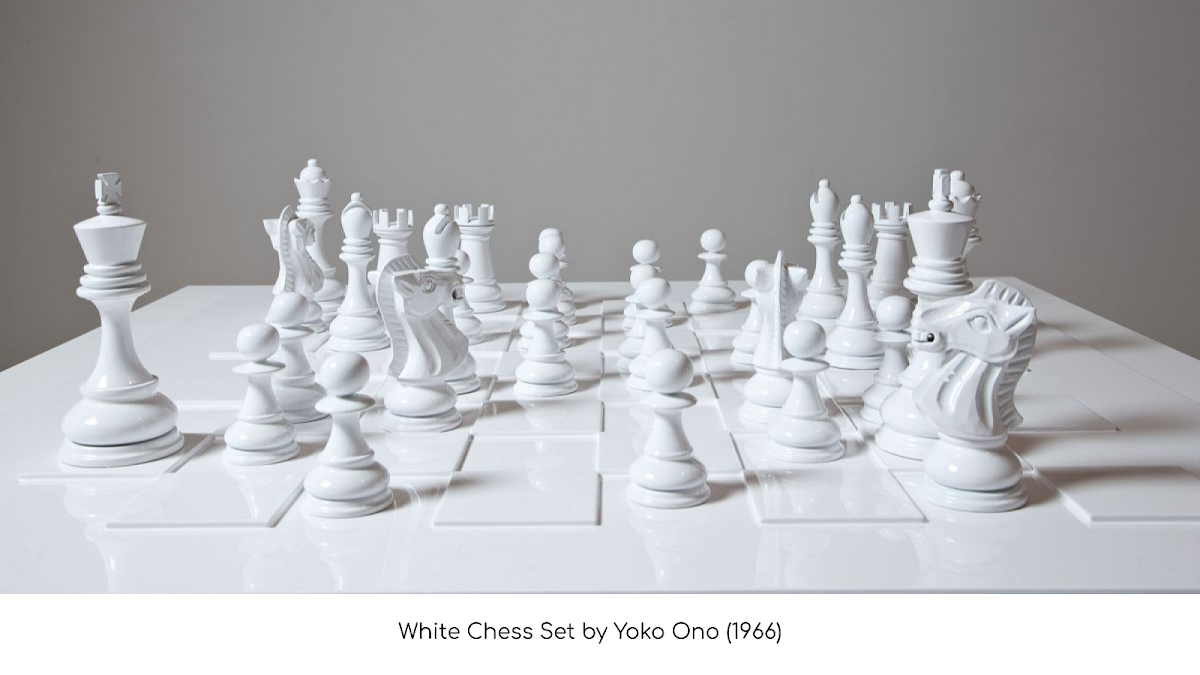

It may be hard to know the impact of unplayed games, their reason to exist. They can function as a beautiful art object, like the mostly unplayable Fluxus games.

They can still make a statement, and communicate with their mechanics and symbolism.

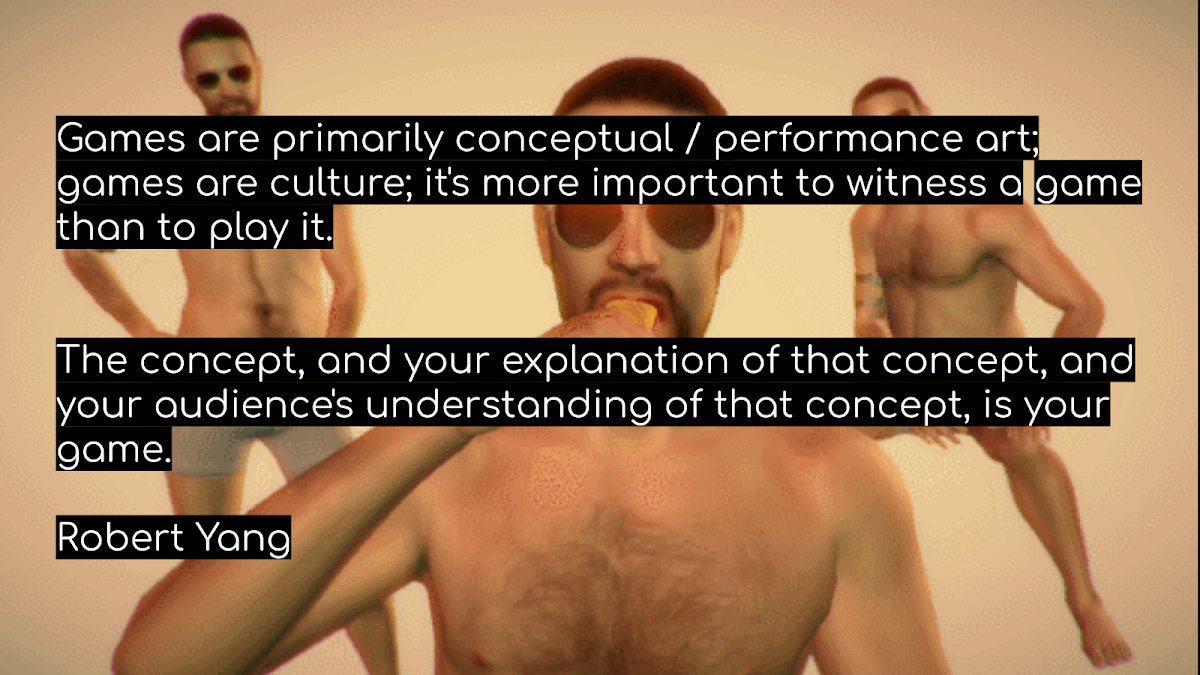

This is a quote from Robert Yang. Robert made several weird gay games that went viral as videos or animated gif. He realized that most people who knew about them didn’t actually played the games (which by the way are usually more dense and interesting than their giffable scenes). He also asked a possibly awkward question: “What if some games functioned better as cultural hearsay? (something you only hear about) What if you designed a game TO BE hearsay?”

Jason Rohrer once made a game meant to be played by somebody 2,000 years from now. It was part of a speculative design competition. But he actually created this game, taking the prompt as a serious design problem. The game was made in metal that would not degrade over centuries. The rules were described with diagrams, in case human civilization disappeared, or English was forgotten And it was buried in the middle of the desert. It was made intentionally hard, but not impossible, to find.

We have pictures of A Game for Someone, but it’s entirely possible that Jason never made a playable game, or that he actually buried it. It wouldn’t matter because it tells an interesting story regardless. This takes me to my final kind of games without players: imaginary games.

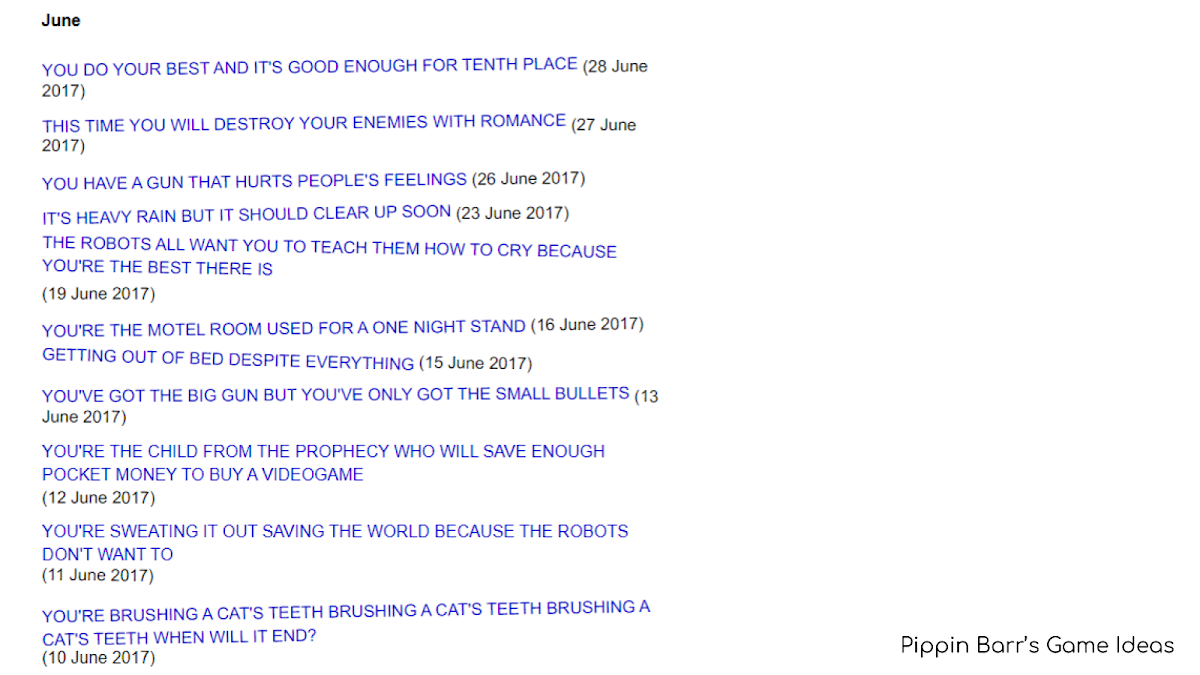

I often post absurd game ideas on twitter. We are all full of ideas we will never have the time or energy to develop. Game artist and scholar Pippin Barr turned sharing game ideas on twitter into an everyday practice. Many game ideas are abstract provocations, some could be starting points for actual games.

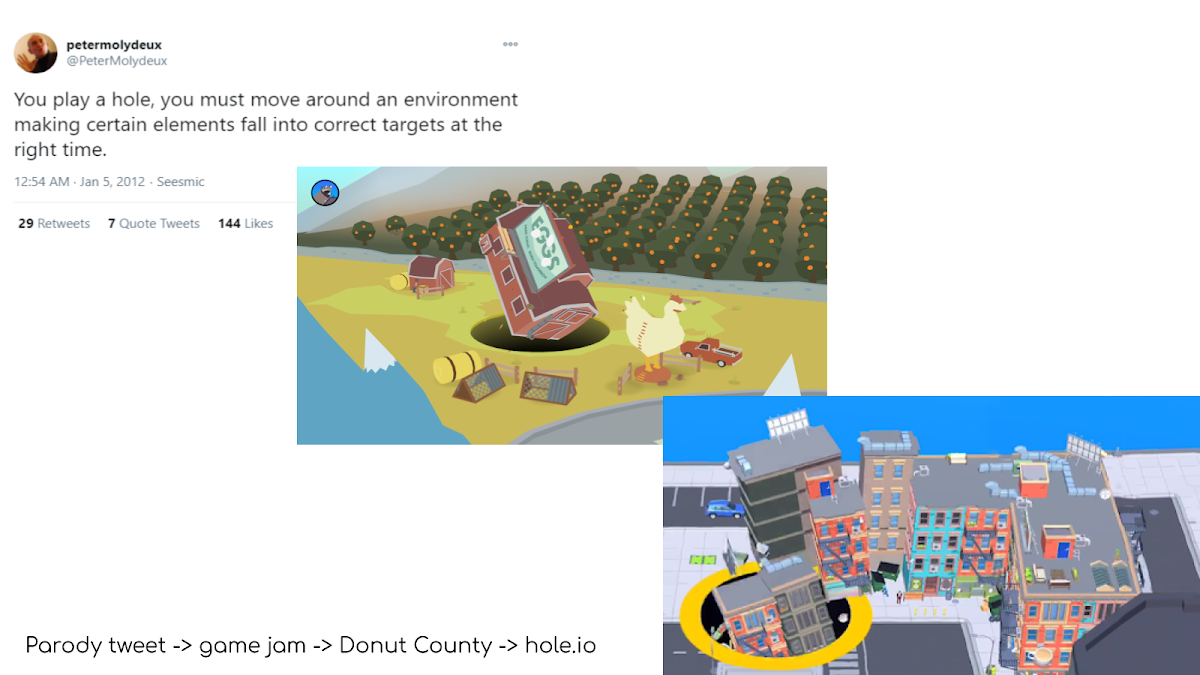

All games start as imaginary games. Occasionally game ideas are picked up by others and become true. It happened to this tweet by the parody account Peter Molydeux.

A game jam was made in his honor. The prototype for the game Donut County by Benjamin Esposito, was inspired by this tweet. In turn, Donut County, while it was still unreleased (and unplayed), was ripped off and turned into a one of the most successful phone games, hole.io. It’s quite different and much worse than the original, but that’s beside the point.

I don’t want this talk to be just descriptive. Since many of you make games I want to offer something “concrete”.

I think all these examples provide ideas for designing games in saturated attention economy. They also stimulate more profound questions about our work as game developers.

Here’s a checklist for you:

What is your game offering beyond interactivity?

Visually, conceptually, socially…

Is your game performable?

Does it give a streamer the possibility to talk over it or joke about while playing?

Can your game be played while doing something else?

Second screen experience / other tab experience

Can your game function only as a gif, screenshot, or documentation?

And are you ok with that?

Can an AI play your game better that a human?

And if so, why should a human play it?

Can your game exist in contexts and spaces that are not currently associated to videogames?

(did you know Atari prototyped arcade cabinets for doctors waiting rooms?)

Does your game need to be played to function in the world?

Which has broad implications on how to make a living with it.

Does your game need to be implemented to function in the world?

Of course you’ll also have to answer the question: what does it mean to “function”? That is: why are you making a game?