These are the slides and the edited notes from a talk I gave at the Games for Change Festival in New York. The talk was targeted to that specific audience (bureaucrats from the nonprofit industrial complex, TED-style technopositivists, game advocates…). Certain parts such as my take on metrics and social change, which may seem obvious to most people, were actually quite inflammatory in that context.

You can find a video of the talk here plus Q&A.

TALKING ABOUT CHANGE

Before I start, I’d like to go back in time for a second:

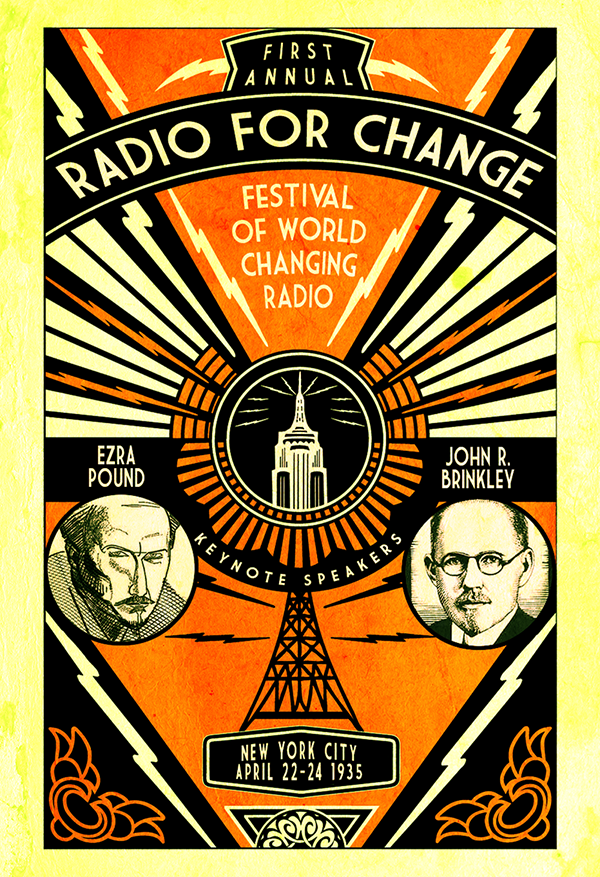

New York 1935. In that year took place the first Radio for Change conference.

In 1935 Radio is a brave new medium with a lot of potential and it’s already changing the world. People are coming from all over.

A delegation of Fascists from Italy are presenting their rural radio program, an effort to bring the voice of Mussolini to underserved communities.

The people who will later create Voice of America are talking about their experiments with short wave radio.

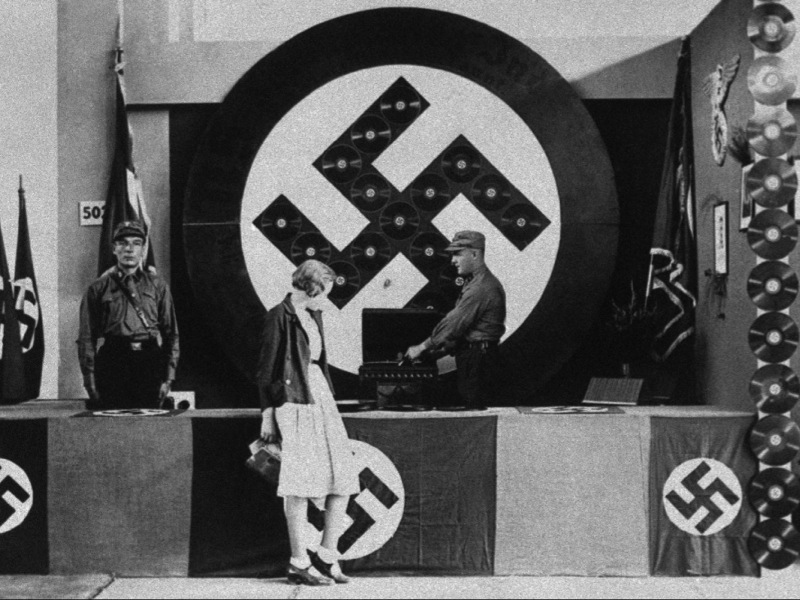

The Nazis are also presenting. They are really into radio.

Goebblels once said: “It would not have been possible for us to take power without the radio”.

At Radio for Change there is a delegation of Soviets.

Young Orson Welles is attending. Here he gets the inspiration for his famous radio adaptation of the War of the World (a couple of years later).

There are some anarchist coming from the Spanish civil war.

Poet Ezra Pound is keynoting about his antisemitic broadcasts.

Professional con artist John Brinkley is giving a talk about his pioneering use of border blaster radio. He set up a super powerful radio station across the Mexican border to illegally promote his quack medicine products, and to advance his political campaign for governor of Kansas.

Of course Radio for Change never happened.

It’s unthinkable that people with completely different ideologies would simply gather around a medium and generic idea of change at that point in time.

And yet here we are now, academia, disruptors from the education industry, DARPA creeps, venture philantrophists, noprofit bureocrats, technocrats, game fundamentalists…

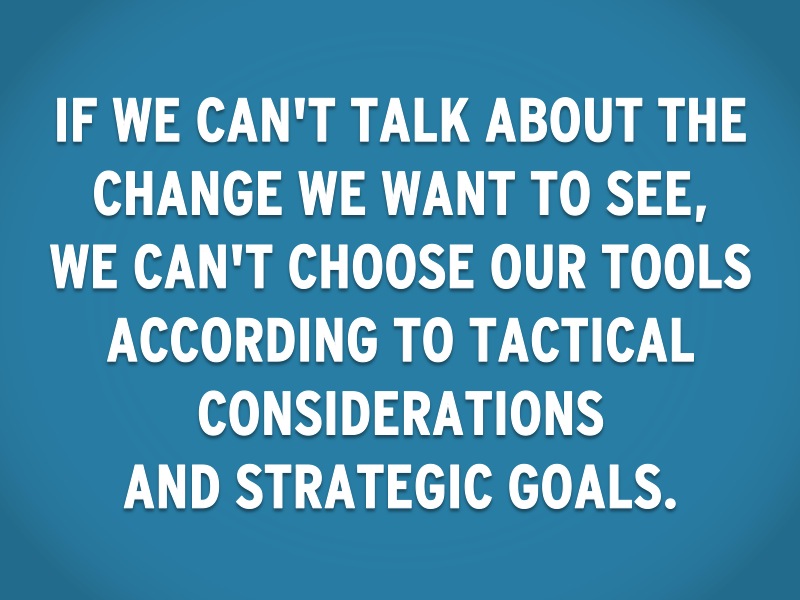

We are working for all kinds of change. Therefore we cannot really talk about change.

We use euphemisms like social good, values, and other progressive terms that don’t offend or scare anyone (especially funders and sponsors).

But we can only really talk about games. It’s the only common denominator.

We are discussing games as general purpose instruments.

And in doing so we are putting the means ahead of the ends.

Here’s my first proposition:

The Nazis embraced radio because, in Germany, at that point in time it was an extremely centralized infrastructure. Perfectly consistent with the kind of change they wanted to create.

THE DELTA

The discourse around serious and transformative games has been stuck in a sort of delusional loop for several years now.

Of course at this point we established that games can be expressive and representational media. They aren’t mere vectors for messages to be dumped into players’ brain.

They are objects we can think with – like moving images, or texts.

They are interfaces between people.

They are conversations that can happen via body language and verbal language, through the clash of conflicting desires, through the dance between chance and skill, through computation and storytelling…

Even single player games are conversations.

I often say that single player computer games are a type of multiplayer games. The designers can be seen as players as well. They are an extreme form of asynchronous, asymmetrical game if you will.

You play with the authors.

Games are multitude.

BUT for serious and transformative games this is not enough.

It’s not enough to be just a cultural form among the others.

Serious games want to transcend this symbolic and relational dimension and be the very embodiment of *actual* change.

This is the delusional loop I’m talking about.

One of the starting points of this narrative was this talk from 2007:

Making a new kind of serious game: Games that are designed as functions with an end result that is a measurable difference in the present state of reality.

Jane McGonigal Erasing the Delta – Games that Accomplish a Specific Task

Games Developer Conference 2007

The delta is the gap between representation and actual change.

And here the keyword is measurement.

The presumption is that social change can be measured in the same way you can measure the calories burned by playing an exercise game.

This obsession with quantification pervades contemporary society.

It’s the basis of the gamification ideology.

And the basis of contemporary capitalism. Late capitalism is less about producing and selling stuff and more about reifying the immaterial sphere (culture, language, relationships, ambitions).

If you can measure something, you can rationalize it, you can optimize it, you can sell it.

If you are in the no profit industrial complex you can get more funding if you demonstrate a measurable impact.

Except the measurement of complex social phenomena is always reductionist and problematic.

We use the Gross Domestic Product to measure the success of a nation disregarding many other indicators.

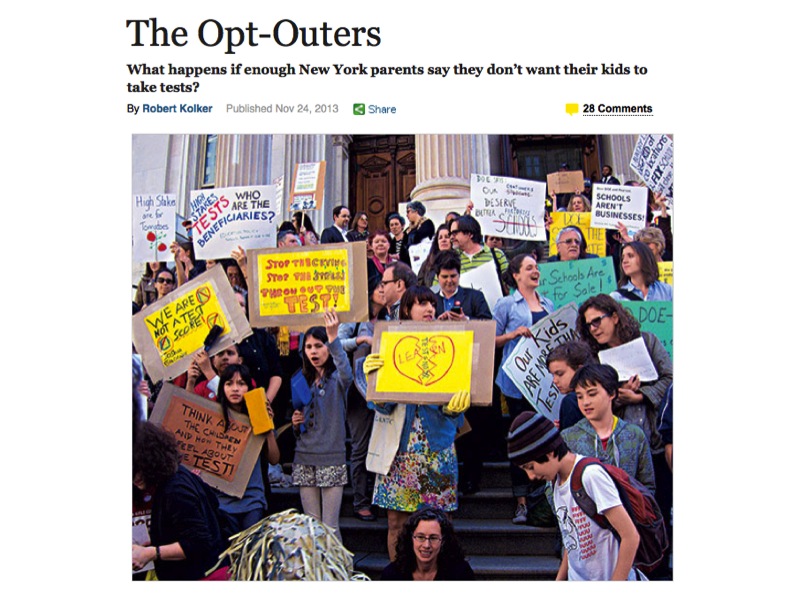

By using standardized tests to assess the quality of learning we turned our schools into bootcamps for standardized tests.

Here’s another simple proposition:

If you can measure it then that’s not the change I want to see.

It’s a provocation of course, I’m fine with games accomplishing very specific tasks.

The problem is that by focusing on measurable goals we narrow our action.

We favor individual change, versus systemic and long term change.

We target burning calories without addressing food politics and food justice.

We try to impose prepackaged behavior protocols rather than facilitating critical thought.

And I’ll go even further:

If your game or technology really works (in this direct and reductionist way) it freaks me out.

If you actually figure out methods to control people’s behavior.

You can bet they will be adopted by governments and advertisers in no time.

You are working for them.

TALKING ABOUT FAILURE

Ok, let’s measure some change.

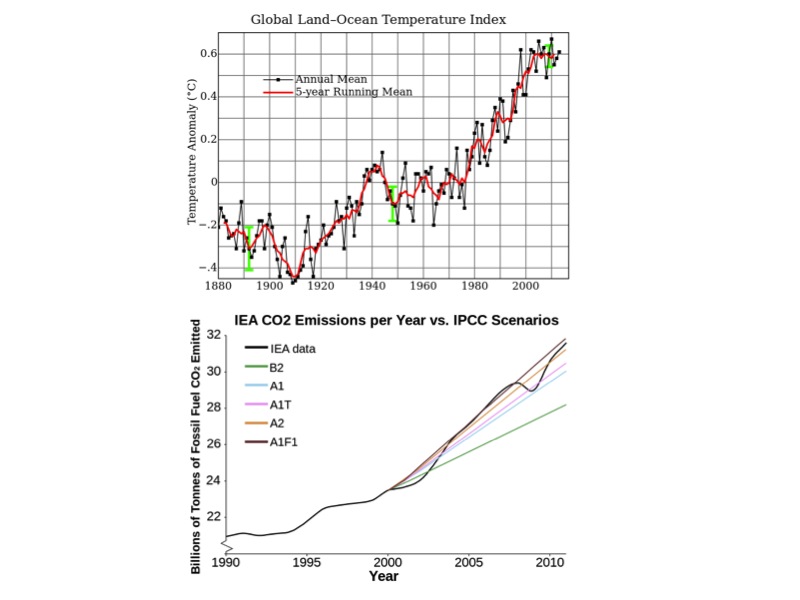

Global warming: everybody is an environmentalist now and yet there’s no encouraging trend.

Scientists are desperate institutions switched to disaster management.

Even talking about global warming is so 2008.

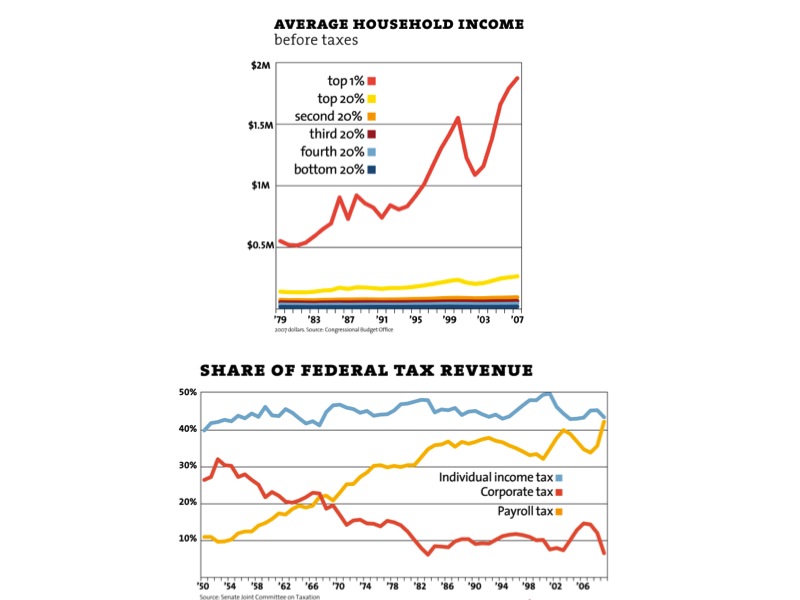

Economic Justice. In all Western nations the income gap is growing in an indecent way.

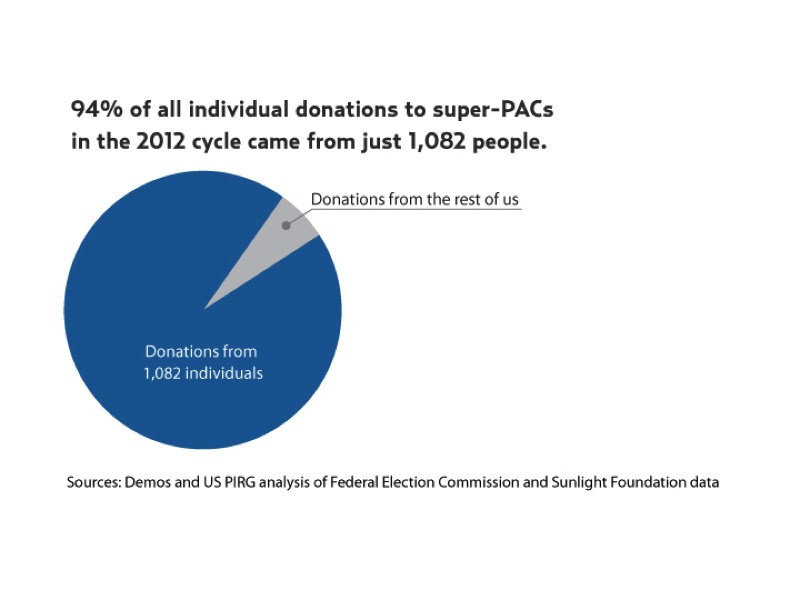

Democracy. Big capitals play an increasing role in politics.

The Citizen United and the McCutcheon rulings extended the legal corruption even more.

People perfectly know that this is corruption and would support strong reforms. Yet, there’s no political support and no sign of policy change.

In other words, if you are anywhere in the progressive spectrum, you are losing.

We are getting our ass kicked.

Sure we advance on formal equality issues, gay marriage, legalization of marijuana, maybe women’s rights.

But only because they depend on traditions, on generational makeup. The silent generation is dying and baby boomers are retiring.

This report came out recently. It tries to figure out why there have been “no significant victories for environmentalism in the United States since the 1980s” despite huge funding to environmentalist organizations.

(For example analysts argued that in 2009 green groups spent more than industry and conservative groups in climate change activities and it was a fiasco. Even Cap-n-trade, which was the moderate capitalist friendly solution, didn’t pass)

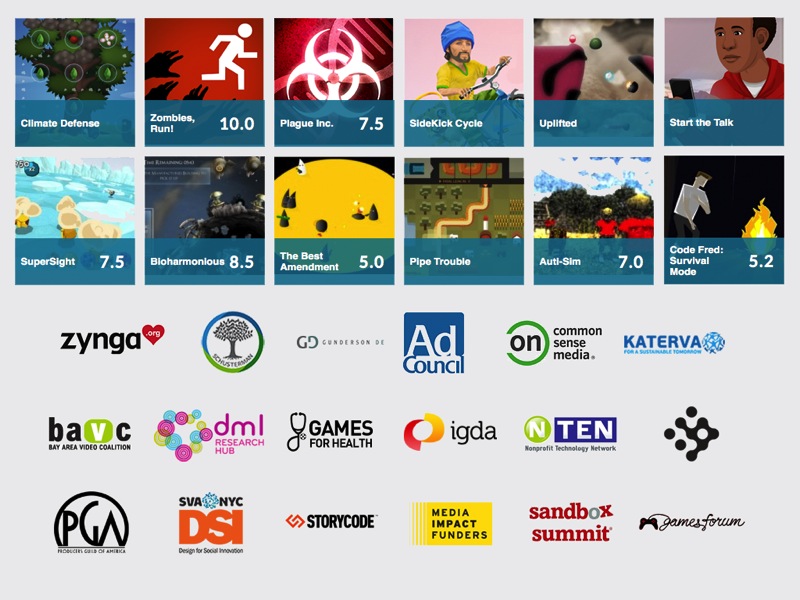

And big, professionalized institutions are the usually the ones that can afford games because games can be kind of expensive to make.

Here are some numbers. I know these cases are a bit dated:

ICED a game about the deportation of immigrants commissioned by Breakthrough.

World Without Oil. Alternate reality game about the energy crisis. I love that project. It’s brilliant but:

Evoke, commissioned by the World Bank Institute. Winner of a Games for Change Award.

500 thousand dollars. $100 per active player.

These are not insanely high prices compared to triple A games but none of the organizations I like actually have that much money to spend on a game.

And even if they did, the big question is:

Is it even morally ok to spend that much money in what is essentially communication and branding?

Maybe this is one of the reasons why the serious games community tries to sell games as *actual* means for change, as a surrogate of organization, policy implementation, or collective action, rather than as mere communication.

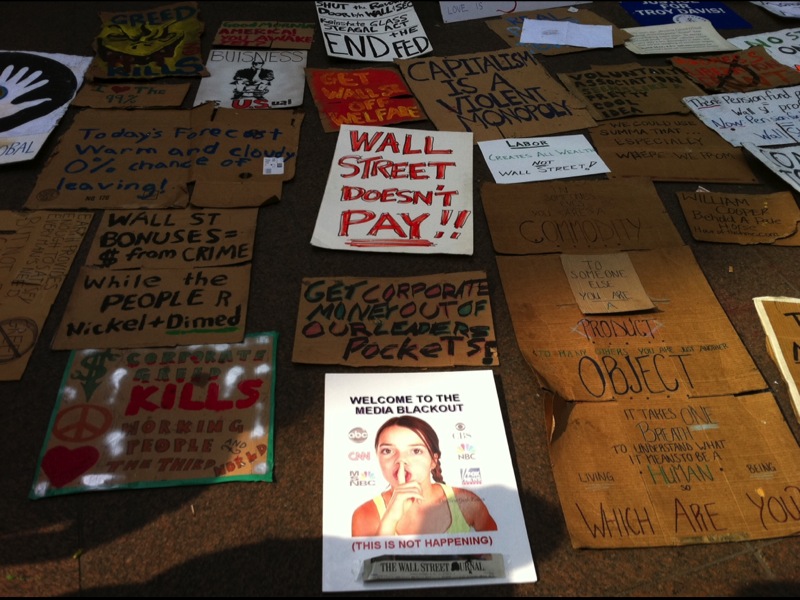

On the other hand, the recent movements that actually set some things in motion like the Arab Spring, Ghezi, or Occupy Wall Street (which managed to reintroduce the idea of class and inequality in the American discourse after decades) were all bootstrapped, underfunded, and not supported by organizations obsessed by metrics and outcomes.

Their tools and technologies were quite basic, the cardboard signs and the people’s mic became iconic.

GAMES OF THE OPPRESSED REBOOT

So what’s my proposal?

I don’t know. I’ve been making games for 10 years now. And I have no idea if they work.

I can pull out plenty of numbers and qualitative feedback. But I have no way to measure their impact.

But hey, how do you measure the impact of the first record by Minor Threat?

There are different stages of social engagement, and we need different approaches.

I’m interested in the Pre-political phase.

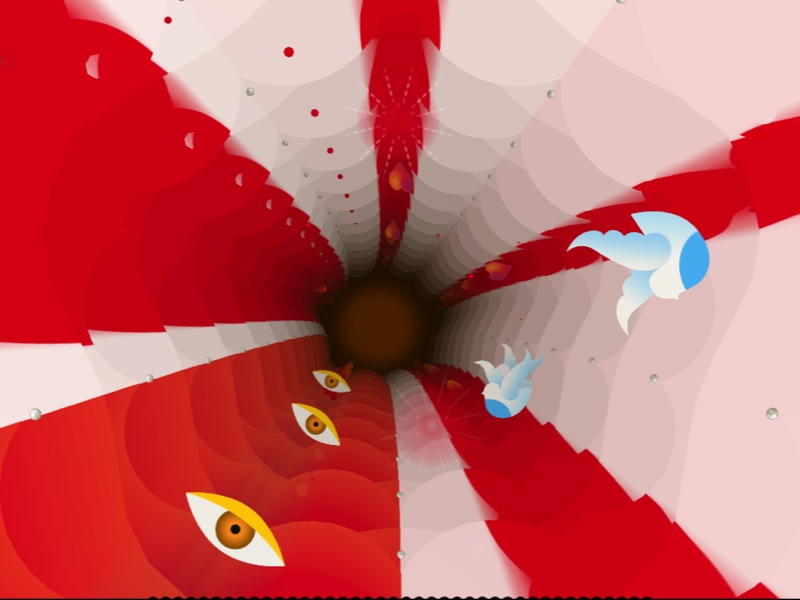

Maybe the “message” of a game is doomed to be lost in the extreme ambiguity of interactive artifacts.

Maybe the “impact” on players is lost in a tangled web of influences, experiences, and biases.

But one thing I can tell for sure: the act of making games about social issues, has always been a profound transformative experience for me.

I came to the conclusion that there is a greater liberation potential in designing games rather than playing games.

I argue that next step of games for impact doesn’t lie in some technological advancement but rather, in helping people to engage with the practice of game design.

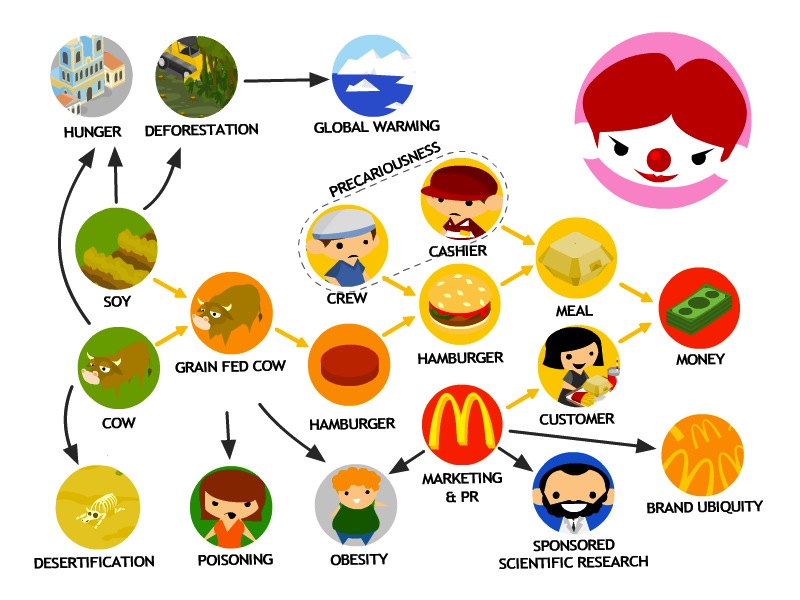

Game design, especially when socially engaged, involves a lot of research and synthesis. What are the actors and the forces governing this system?

What are the internal relationships?

What are the limits of the player’s agency?

This conceptual (and not just technical) tools is what we practitioners can share.

Designing game has a couple of terrific extra outcomes:

First: by designing games you acquire the tools to demystify all games. To play critically.

Second: by democratizing game design you don’t have to look for big funders.

Games are expensive to make but also not. I’ve never spent more than 100 dollars on my games.

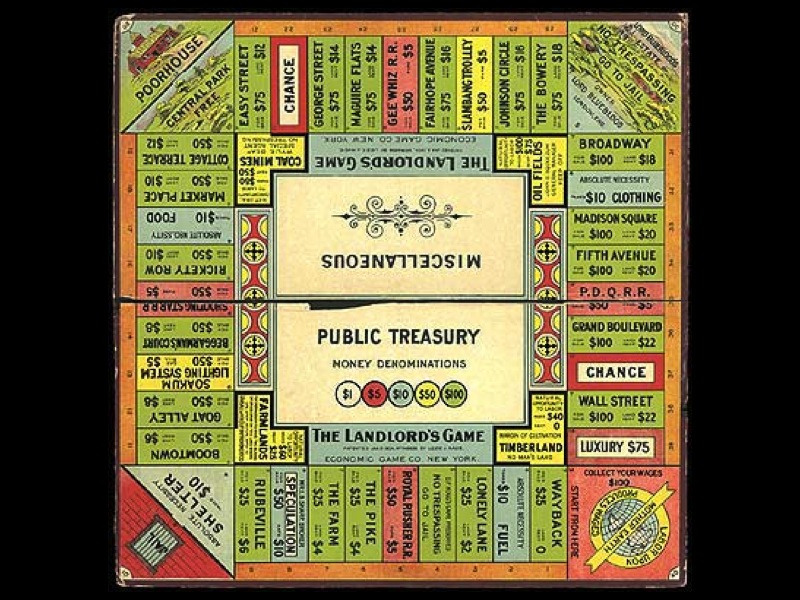

There are plenty of digital tools. And non professionals have been making and adapting games (even games for change) since forever.

As Zach Gage said yesterday, every child is a game designer.

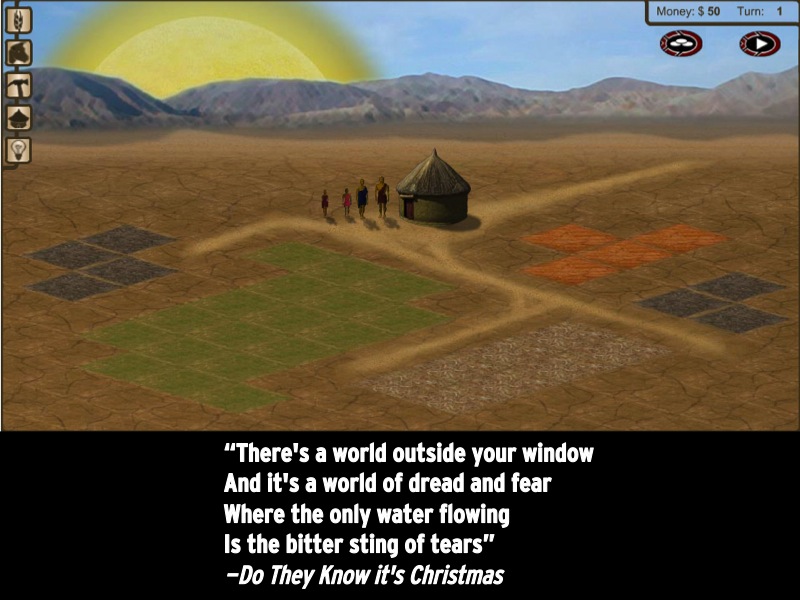

Third: by just facilitating the creation of games you don’t incur into typical fallacies of the white savior industrial complex. Like the mis-representation and objectification of others.

This makes me think about another keyword in this industry: empathy.

If you want to convince privileged people to donate you have to make them feel bad.

But empathy is almost inevitably patronizing, it presumes helpless subjects who can’t speak for themselves. And privileged subjects i.e. “us” that are somehow separated from them.

Oppression is fractal.

Most of us (the 99% of us), are both oppressed and part of a system of oppression.

Anyway, here’s my last proposition:

Which is probably a terrible idea if you want to be a professional in the social change industry.

I want to conclude by mentioning an initiative I’ve been helping to coordinate in the last two years.

It’s not a solution but a small contribution and a possible alternative model. It’s a series of workshops called Imagining better futures through play.

It’s a track of the Allied Media Conference, a meeting of media activists and community organizers that happens every year in Detroit.

There, we prototype games for change, with or without computers. We break them, we reassemble them.

And here’s the most important thing: at the Allied Media Conference, games are not the common denominator like at Games for Change.

You can go to workshops on creative placemaking, printmaking, organizing against surveillance, transforming the justice system, and so on.

We all roughly agree on the kind of change we want to see.

And based on that shared vision, we figure out the media and the strategies we need.