This is the transcript of a minitalk I gave at Lost Levels 2014, an “unconference” happening during the Game Developers Conference (maybe a bit too square and academic for that casual environment). It’s a topic I’ve addressed in every single talk in the last 10 years or so, but I thought it could benefit from a bit of framing and some nice pictures.

In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

-Jorge Luis Borges’s “On Exactitude in Science”

This short story is often quoted regarding the map-territory relationship.

You may have heard the expression “the map is not the territory”: a 1:1 map would be absurd and useless. A map is used to capture only certain features of a subset of territory.

Digital territories are similar to maps. They are not functional, they don’t typically employ sampling (although I suspect 3d scanning techniques will be used more and more in the future)

but they do attempt to model reality, to simulate familiar features of a territory.

Vice City and San Andreas are trying to capture the look and feel of New York and Los Angeles

without recreating them street by street.

Digital territories have boundaries too.

They are fascinating places.

Artist Mary Flanagan created a performative machinima exploring the borders of Second Life.

Walking for hours at the edge of these virtual real estates, where the digital landscape glitches away.

Virtual photographer Robert William Overweg made a series of surreal landscapes called the end of the virtual world documenting the boundaries of designed territories.

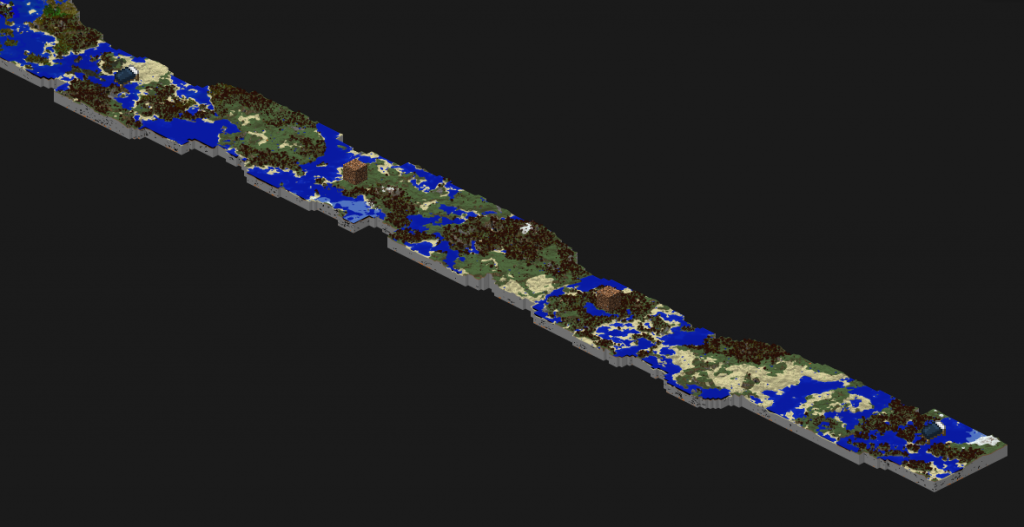

Even procedurally generated worlds like Minecraft are not really infinite.

According to the developers “there’s no hard limit in Minecraft, it will just get buggier and buggier the further our you are” (I presume that’s due to the limits of the floating point variables used to generate the worlds).

To verify the claim, Minecraft aficionado Kurt J. Mac is on an epic journey to explore these mythical “far lands”.

We are all familiar with the notion of invisible wall in games.

we all tried at some point in time to get into an area that was not just blocked but simply not designed. Doors that don’t open, inaccessible forests, very steep cliffs, invincible bedrocks, suspicious roadblocks, and so on…

The art of level design includes the ability to disguise these boundaries, to divert the player’s attention away from these unsettling edges.

The movie Truman Show is all about managing the protagonist’s attention toward the self-contained world, and culminates with Truman breaching the invisible wall.

Beyond the spatial dimension, on a more conceptual level, games have boundaries too.

Games can be seen as cognitive maps. What they simulate is limited both in scope and quality. We want to display only certain kinds of isomorphism with actual systems and phenomena.

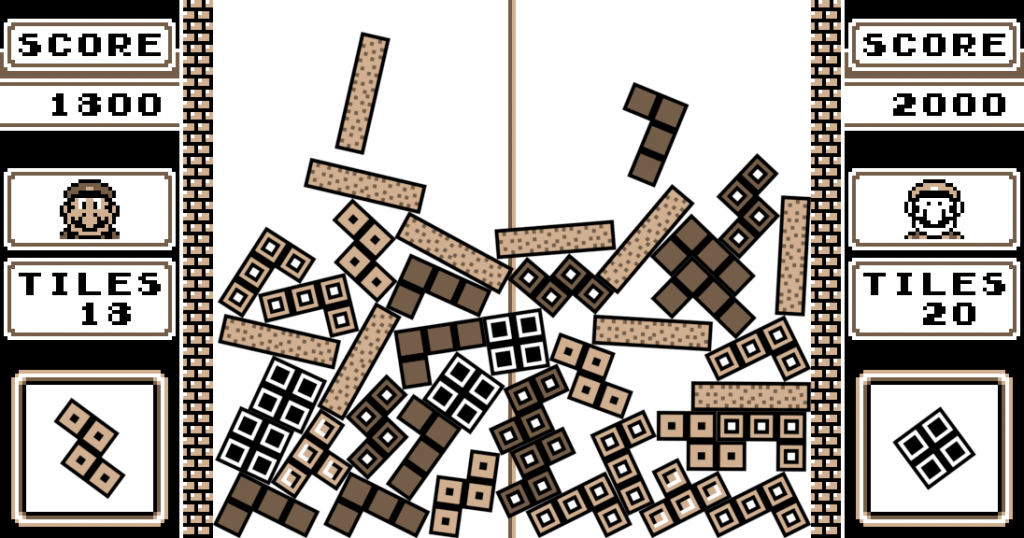

The physics system in Tetris is extremely stylized but it still models gravity and the behavior of rigid bodies as observed on our planet.

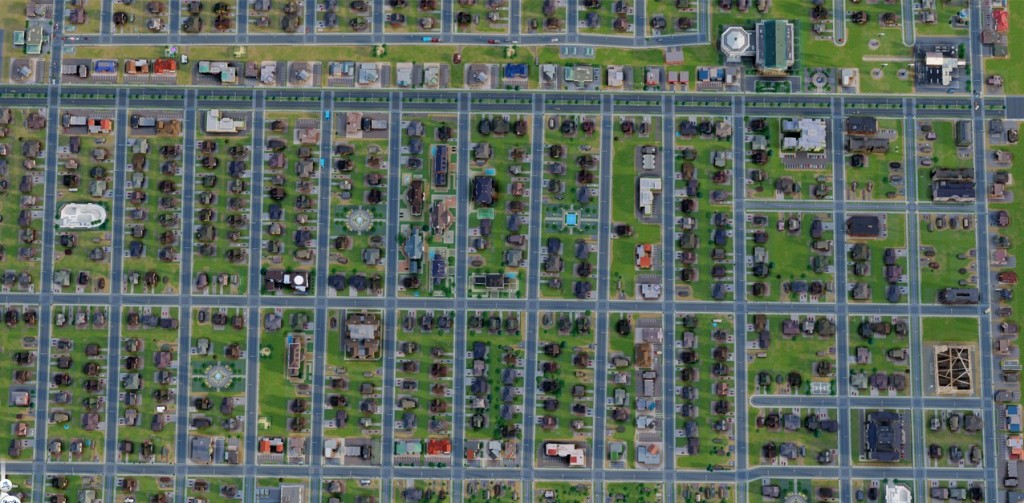

Simulations like the ones from the SimCity series are complex and emergent. But they model only certain aspects of a city and city planning.

I always say: you don’t really see racial dynamics in simCity. Why is that?

Racial tensions, gentrification and white flight have been crucial component of the decline of big American cities. The designers simply decided to draw the line there – that is out of the system.

And if you are making socially aware games and simulations, these are the hardest choices to make.

In my Marxist(ish) game about automation and industrialization I couldn’t find a way to include the issue of reproduction of labor power. That means that a whole tradition of feminism didn’t make it into the game.

Like in level design, there are all sort of strategies that can be used to deal with the boundaries of a simulation.

One obvious way is framing: managing the players’ expectations through storytelling or by leaning on a genre. If you make a tactical dogfighting arcade game like Luftrausers players will not expect to have a strategic dimension. They also won’t expect the game to address the emotional trauma of war.

Another way is to point at the external world without simulating it.

System analysts sometimes use cloud symbols to represent the inflow and outflow of resources in a system – the cloudy world we don’t need to include in our model (in information system it’s often the larger Internet).

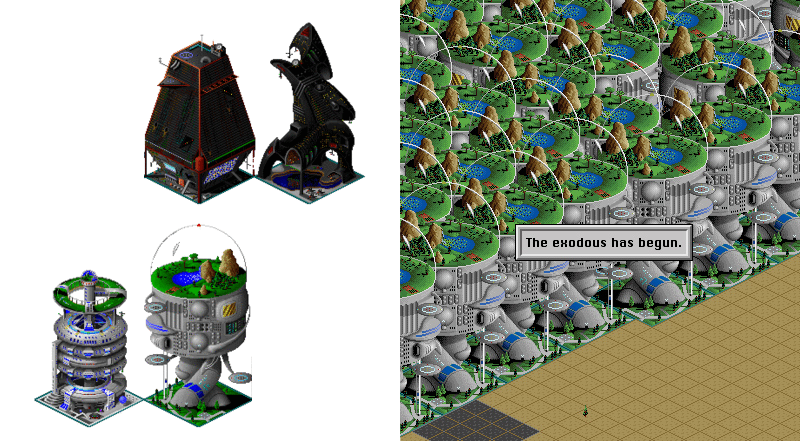

In SimCity you may have highways connecting your region with the rest of the world.

When the city reaches the physical population limit you can build arcologies: giant utopian/dystopian cities within the city. And when there is no room left for arcologies, the futuristic buildings will simply take off and disappear into space, the ultimate output for our closed ecosystem. The built-in growth imperative of the series can’t be challenged by issues of limited resources or overpopulation.

Random events in both analog and digital games are often used to suggest there is a larger chaotic world outside the core system. In a game like monopoly you have community chest and chance cards. They are meant to introduce an element of chance of course but also to point to a larger world (or “community”) outside the game economy, a world of taxes, corruption, hospital fees etc.

I recently wrote a critique of the upcoming game Prison Architect

(you can find it on Kotaku) in which I talk about not only *how* the prison system is characterized, but also about what is left out of the system, and how these removals are ultimately ethical and political choices.

As designers we should be constantly aware of where we draw these boundaries, because it’s easy to mistake scoping for a purely technical choice.

Of course the problem is not in the boundaries themselves, but the in way they are outlined or disguised. A narrowly focused game like Papers Please is more honest, more transparent in its limits than a maximalist open world like GTAV which strives to give the illusion of unlimited affordances.

It’s fine to show edges, inflows or outflows. It’s fine to declare that the game has a focus.

Nobody wants or need a 1:1 map.

Rather, we need a multiplicity of cognitive maps, exploring a multiplicity of aspects,

from a multiplicity of point of views.