This is my second post on Empyre, a longstanding discussion list for artists, programmers, and curators of new media art. The theme of the month is “Videogames and Art: Incite/Insight”. You can check the March archive here.

Here I talk about Molleindustria in relation to the context in which it started (almost 10 years ago) and the current trend of gamification. This is meant to be a conversation starter, not an essay.

Molleindustria is a project about games and ideology, it’s a bit of art, media activism, research, and agitp[r]op.

The idea is to apply the culture jamming/tactical media (remember tactical media?) treatment to videogames: speading radical memes and, in the process, challenging the language of power, the infrastructures, the modes, genres and tropes of the dominant discourse which was omnipresent in videogame culture.

The half joke is that I came up with Molleindustria because I failed at starting my own television. In the early zerozero – mid Berlusconian age – we had pirate TV stations popping up in all the major Italian cities in what came to be known as the Telestreet movement. It wasn’t just television with radical content, but a radically different way of making television.

There was a nice medium-is-the-message / form-follows-content thing going on, resonating with software, net.art and hacker culture as well.

There was this idea that the political sphere was boundless: something we do, and we are subject to, every day and every moment. The half-naked show girls on prime time television, the charming millionaires of the soap opera Dallas, the software, the protocols, the fantasies coming from the booming-and-busting Silicon Valley were no less political than the occasional vote or the sanctioned spaces for political debate.

And, of course, the demonstrations in the streets, the boycotts, the occupations, the strikes…

I am very familiar with Gonzalo Frasca’s work which was previously mentioned on this list and from which I borrow the title of this post. I launched the project in 2003, the same year September 12th came out and he started to write about videogames with an agenda with Ian Bogost.

One thing I share with both of them is the idea that videogames are representational media. They are always about things. There is, of course, a gradient of abstraction in that a game like SimCity is unquestionably about cities (or gardening) while a game like Tetris is about more general themes such as order vs disorder, control & optimization, or the tragicomical limits of human cognition.

The less abstract are the games, the more they tend to be problematic and fall under scrutiny. There is a lot of literature discussing the urbanist ideas advanced by SimCity or the portrayal of contemporary and historical conflicts in first person shooters or strategy games.

To interpret a game and to make games that mean something, people use a variety of approaches.

Some aspects can be tackled with traditional storytelling and narratology. For example, later this week, pop-feminist Anita Sarkeesian will launch the first installment of “Tropes vs women in games”, an online video series dissecting the representation of women in videogames (edit: now released).

However, there are aspects of games that can’t be fully understood by simply breaking down characters and plots. Games, simulations and interactive media are systems of rules, and these rules produce meaning as well: they define the relationships between the purely representational bits (images, sounds, text…) and the agency of the players within the system.

To be honest, we are still trying to figure out how this procedural rhetoric actually works and how people interpret these “texts” with so many moving parts. But that’s the fascinating part.

I’m interested in promoting this kind of procedural literacy through my games. I believe games can get people used to “think in systems” and that a holistic, ecological, non-reductionist way of thinking is desperately needed in our [cliche’ alert] increasingly interconnected world ravaged by global crisis.

Part of this literacy consists in understanding that digital and non digital models are informed by ideologies and systems of values (when it comes to scientific simulations the story is a bit more complicated). They are artful depictions of reality, and as such, we should describe them not in terms of how “realistic” they are, but in terms of the arguments they deploy and the narratives they support within the larger context. This is, by the way, the reason I often use satire, cartoonish styles, and a rather overt authorial “presence”: to defuse the temptation of interpreting these games as objective.

I feel like I have to mention the issue of representation because there is another trend, another way to conceive and use games that has more to do with behavioral change. The marketing power fantasy referred as “gamification” is part of this trend, but also slightly more legitimized endeavors like the many exercise games pretending to fight obesity.

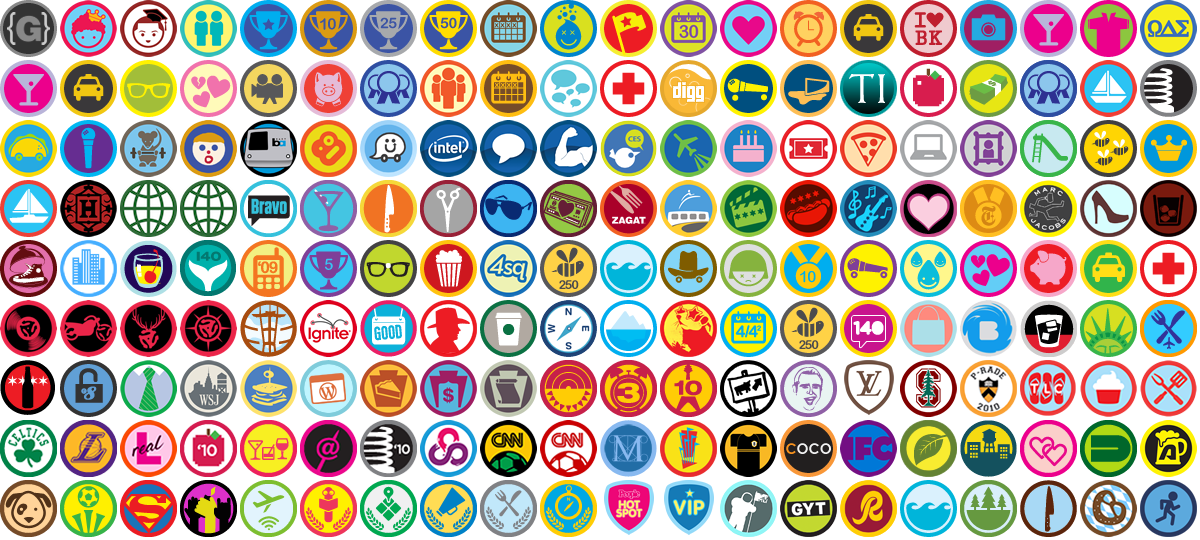

This approach is less concerned about the semiotics and the aesthetics of games, and more focused on games as systems of incentives to produce actual, quantifiable change in the way players behave outside of the game (if there is an outside). If you are not familiar with gamification and the like, imagine attributing arbitrary points and rewards to certain behaviors, pushing people to voluntary monitor these behaviors, and then creating the conditions for competition/self-evaluation based on the score system.

Commentators like Ian Bogost have called bullshit on gamification and I largely agree. But having worked in marketing in the past, I’m quite familiar with the structural hype cycles of the field. You have people overselling techniques meant to oversell services and products. Everybody is lying to everybody else on multiple levels, intra- and extra-corporate. But as a whole the advertising system works because it succeeds at pervading every corner of the mindscape with the discourse of consumption.

To me it is not too crucial to find out whether or not you can control people through game-like systems. What’s more important is that this fantasy is out there, strong and loud. Governments and corporations are investing lots of money in this idea.

Feasible or not, this is the object of desire of contemporary capitalism and as such it’s worth investigating.

Is the fantasy of gamification a testament to the decline of money as the general, all-encompassing incentive to regulate human relations?

Could it be a premonition of the next power paradigm? We went from a disciplinary society (the stick) to a society of control (mass surveillance). Is the society of the incentive (the customized carrot) next?

Is gamification a tension toward the measurement of the unmeasurable (lifestyle, affects, activism, reputation, self esteem…), being measurement the precondition of commodification?