In no particular order.

Dys4ia

There have been a few overtly autobiographical games in recent years (Jason Roher’s Gravitation and Papo and Yo come to my mind) but nothing has been as direct and vivid as Dys4ia.

Anna Anthropy’s playable diary revolves around her experience with hormone replacement therapy. Every chapter is a minimal game that cleverly employs low-level systems of interactions (controls, collisions, movements in space, micro-challenges and so on) to express a range of visceral states like frustration, stress, humiliation or relief.

Beside being a powerful piece in itself, Dys4ia is also a perfect proof of concept for Anna’s book Rise of the Videogame Zinesters a passionate call to embrace game-making as mean of empowerment and self-expression. And we are not talking about the narcissistic kind of self-expression, or the bourgeoisie idea of investigating the “human condition” through the Author’s personal journey. Anna’s experience is still quite uncommon, not often told, and hotly contested. The idea of a multitude of DIY game makers performing their identity through games, connecting with their communities with games, speaking in games, is the ultimate challenge against a games industry that is still unacceptably white, male and privileged.

The personal is always political, but in some cases more than others.

Link

Proteus

The commercial success of Dear Esther this year proved the mainsteam palatability of not-games, a loose category of game-like works not centered around rigid goals. In most not-games the lack of gameplay has to be balanced with a high quality storytelling, a powerful soundtrack and a visually stunning environment to make the exploration intrinsically rewarding.

Like Dear Esther, Proteus is a first-person exploration game set on an island, but that’s where the similarity ends: you won’t find an elaborate spatial narration, ultimately linear like a Disneyland ride; you won’t traverse a beautiful photorealistic landscape, ultimately dead like a Hollywood set.

Ed Key and David Kanaga’s creation is a colorful, highly stylized synesthetic universe to explore freely in time and space. Walking into a spring shower will add a layer to the droney soundscape, approaching the shore will awake pixelated crabs producing generative percussion… For the task-anxious gamer, there’s not much to do, beside discovering the rich ecosystems of sounds and witnessing some time-warping magical events.

For everybody else, this is a new way to experience an immersive virtual environment.

Link

Dog Eat Dog

I instinctively kickstarted this game earlier this year and quickly forgot about it until I met the designer Liam Liwanag Burke at the Allied Media Conference. After a couple of intense sessions I completely changed my opinion on role-playing games.

Dog Eat Dog is a story-game, a kind of short-form RPG that doesn’t require continuous dice rolling, tedious character creation, tacky miniatures, rummaging through manuals and enduring campaigns. It doesn’t even need a devoted dungeon masters or pre-game preparation since the setting is defined collaboratively.

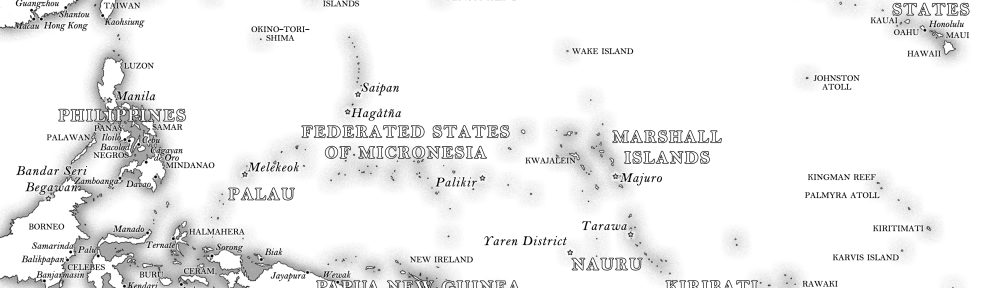

Dog eat dog provides a simple system to enact a colonization scenario, with one player assuming the role of the “colonizers” (as a whole) and all the others playing as “natives” (each one playing one character). The features of both cultures are negotiated at the beginning and further developed during the game. Although the author designed the game as a way to reflect about his Pacific Island heritage, there’s no built-in historical constraint to the setting: we’ve played sci-fi stories reminiscent of Avatar as well as anthropologically-correct fantasy scenarios.

The colonizer tends to take the initiative describing the first contact and forcing the natives to react. Conflicts are resolved by consensus of, more rarely, by dice rolling. After each narrative arc the actions of each players are evaluated according to a developing set of “rules” typically representing the colonizers’ worldview. The first rule is always “The Natives are inferior to the Colonizers” and new ones are added to the list on the basis of the events happened on each scene. For example a new rule may state that “trees are unlimited resources” after the colonizers clear-cut an entire forest and dismissed the concerns of the villagers.

A simple economy of tokens makes sure that the conflict is always tense without encouraging excess on each part (you can read a more detailed explanation here). In fact the most interesting stories are the ones in which colonizers are not looking for direct confrontation and the natives are tempted to assimilate. The ambiguous and fluid gameplay also ensures that no player approaches the game with the competitive gamist mindset. After all, the goal of the game is to develop a meaningful, tragic, compelling story together.

Link

Diamond Trust of London

Jason Rohrer’s long-awaited Nintendo DS game has been penalized by many factors: a long and difficult approval process, an end-of-the-cycle hardware, the unusual 2-player local setup, the grave-sounding theme, and -possibly- the author’s reticence to create his own little hype-machine and compete in the increasingly crowded, over-kickstarted, white-noisy indie scene.

It’s a shame because Diamond Trust of London is Jason’s most elegantly designed game to date. It plays like a euro-style boardgame: few explicit rules (that you have to know before you start), short game sessions, and a deep mathematical core made more digestible by a recognizable theme.

Instead of the idyllic merchant society of Settlers of Catan or the edulcorated colonialism era of Puerto Rico, Diamond Trust is set in a very precise historical moment: Angola in the year 2000, specifically in the last months before the Kimberley Process establishes stricter regulations for diamond trade in Africa.

However, you won’t be lectured about the ugliness of blood diamonds and on the nefarious European influence on the continent. Diamond Trust delivers the “message” exclusively through a gameplay of deception and bribery. Diamonds simply appear on the market, money and gems pass from a pocket to another quietly… don’t ask any questions.

It’s a very tight psychological game that presents the world from the cynical, detached perspective of the Homo Economicus. The harsh reality left out of the simulation is what really matters, but it’s also what can’t be easily reduced into a formal system.

Link

Little Inferno

It’s hard to believe that three of the most talented and successful independent game developers put so much time and love into a game about watching things burn, collecting magical money, and then buying more things to burn. Yet, it makes kind of sense that Little Inferno itself is a finely crafted, sophisticated, and utterly pointless piece of technology to be consumed in few hours nihilistic play.

It’s a sign of maturity when a cultural form starts to interrogate itself. Little Inferno is not a game “about games” in a self-celebratory kind of way, it doesn’t drop nostalgic references nor manipulates familiar gaming conventions. Instead, it forces players to look beyond its fatuous gameplay, beyond the virtual fireplaces. It point inwards, into the dark heart of 21st century gaming, embodying the compulsive drive to monetization and the behaviorist science of rewards perfected by online gambling corporations like Zynga. It points outwards, at the larger schemes of planned obsolescence that drive – and are driven by – the games industry; it points at the social context of games: the fireplace, ancestral center of sociality, which has been replaced by radio, then by television, then by game consoles in an increasingly solitary, mediated and commercialized experience.

Link

Starseed Pilgrim

In the open-minded, novelty-starved, highly-interconnected indie community, innovative titles rarely go unnoticed. Yet, this seems the case of Starseed Pilgrim, a dizzyingly clever “abstract gardening” game lost in an ocean of unremarkable puzzle platformers.

The core gameplay consists in growing convoluted structures in order to reach remote keys while escaping a dark matter devouring the level block by block. The task involves a lot of planning, seed saving, and quick decision making. Explaining all the rules and the properties of the seeds would spoil the joy of discovery; after playing for hours I’m still finding new mechanics and strategies. Deceptively minimalist and finely sonified, Starseed Pilgrim is everything I want to see from a puzzle game: emergent gameplay, dazzling depth, playful exploration, and no pre-designed solutions.

Link

Cart Life

Although technically published in 2011, Richard Hofmeier’s magnum opus only started to get noticed this year, after numerous personal endorsements and in-depth analysis.

In essence, Cart Life is a “working poor” life simulation that puts you in the shoes of a single mom or a migrant man trying to make a living as a street vendor while dealing with your troubled personal life.

Cart Life is not an easy game: hard to learn, impossible to master, open and sprawling like no other indie game, frustrating and gloomy. And yet, it somehow manages to surprise and reward the committed player with fleeting moments of sheer beauty.

The brilliance of Cart Life is in the way it puts storytelling and exploration in direct competition with the brutal resource management gameplay. There is an economy of material necessity made of debt, logistics, paper napkins inventory, swift espresso-making gestures and a completely separated “human economy” (in David Graeber’s terms) of relationship, reputation, love and care. The numeric, formalized, computational core of the game on one side, and the loose, narrative, player-driven component on the other. It’s a great use of the so-called ludo-narrative dissonance for an expressive purpose.

It’s hard to convince you that Cart Life is worth your time because the feeling of wasting your time is a crucial part of the experience.

Wondering if Cart Life is worth playing is a bit like wondering if certain lives right below the poverty line are worth living.

Yes, they are.

Link