This talk was delivered as keynote for the Art History of Games conference, that took place during DiGRA 2013. While the infamous Can Games Be Art? question is now being carefully avoided like an inappropriate text you sent while drunk, some references and questions may still be valuable to the world beyond the small group of scholars that gathered in that hotel basement in Atlanta. It’s a minimally edited transcript/note dump, please forgive the informal tone.

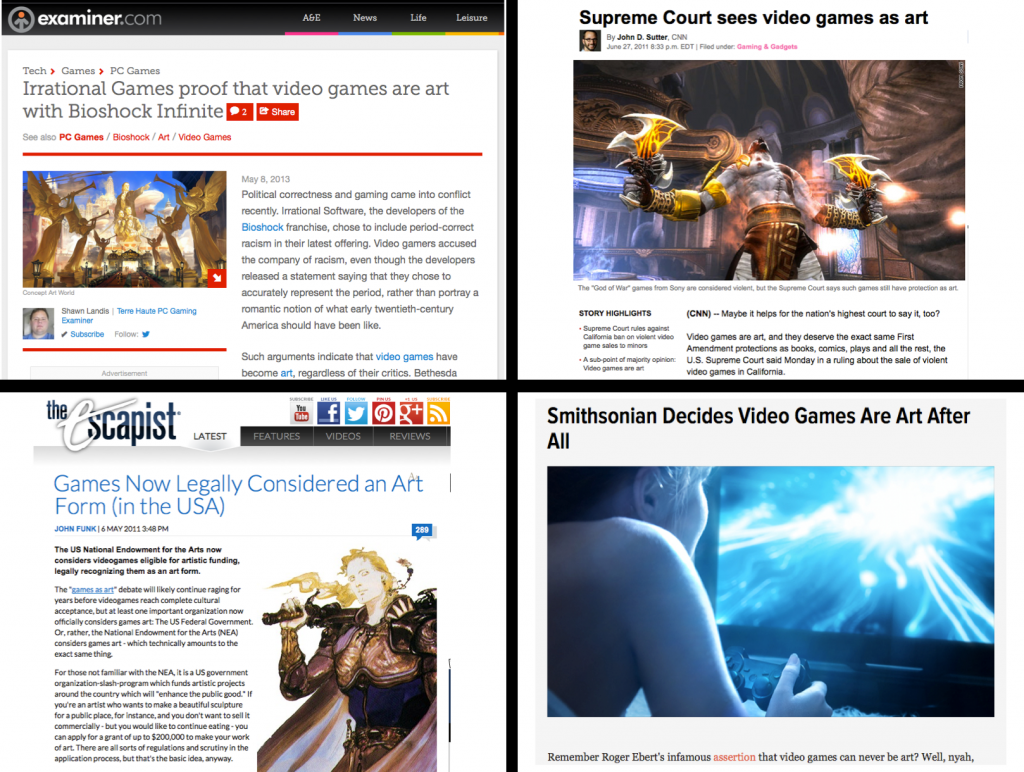

In the last few years, if your filter bubbles include gaming circles you probably have witnessed the many collective cheers, the vuvuzelas, the stadium waves, raising upon every glorious step of the videogame medium toward high-culture acceptance.

Legally art, proof of art, the Supreme Court…

Thislanguage of legal validation is quite alien to the usual art discourse. Artists are not typically looking for proofs and evidences that demonstrate that what they do is actually art. They just… make art.

And if the general or specialized public is perplexed or hostile that could even be a good sign, a sign that they are breaking new grounds. All these articles, and there are many more, usually start with a reference to film critic Roger Ebert and the claims he made from 2005 onward.

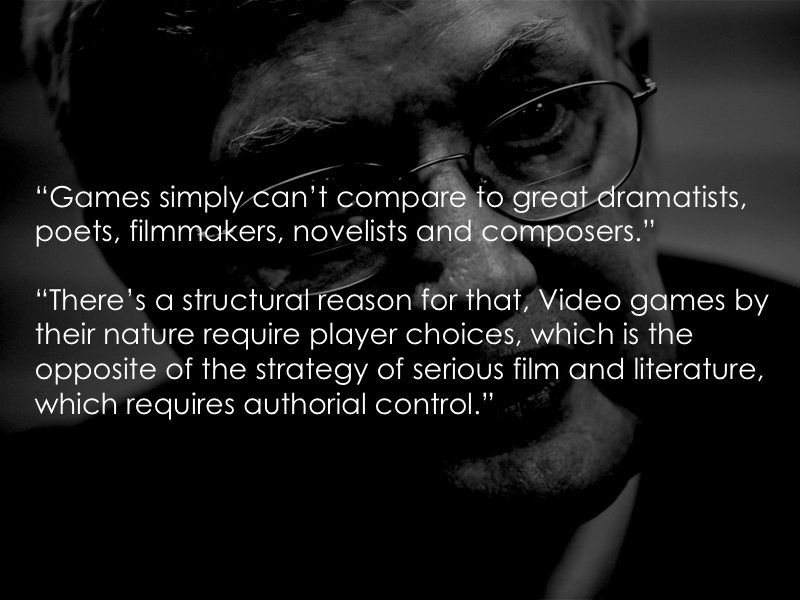

This essentialist and structural argument is so flawed that, as scientists would say, “it’s not even wrong” so I won’t spend any time discussing it.

Now, across the pond in Europe, we’ve never heard of Roger Ebert so our reaction was like “whatever old cinema dude on the Internet”. But here, I found out, Ebert is not just an authority in his field: he is a kind of Americana icon like Twinkies or colorful license plates.

And because he was so loved, he suddenly became the villain. It was as if a mutated Mr. Rogers suddenly started to use racial slurs. Americans just… could not ignore that.

What really matters is that: something new happened. These statements forced a generation of North American game developers, game critics and players to confront the mysterious Art Thing. Possibly for the first time in their lives. Their honor, their reputation and their favorite pastime was being attacked by a prominent tastemaker.

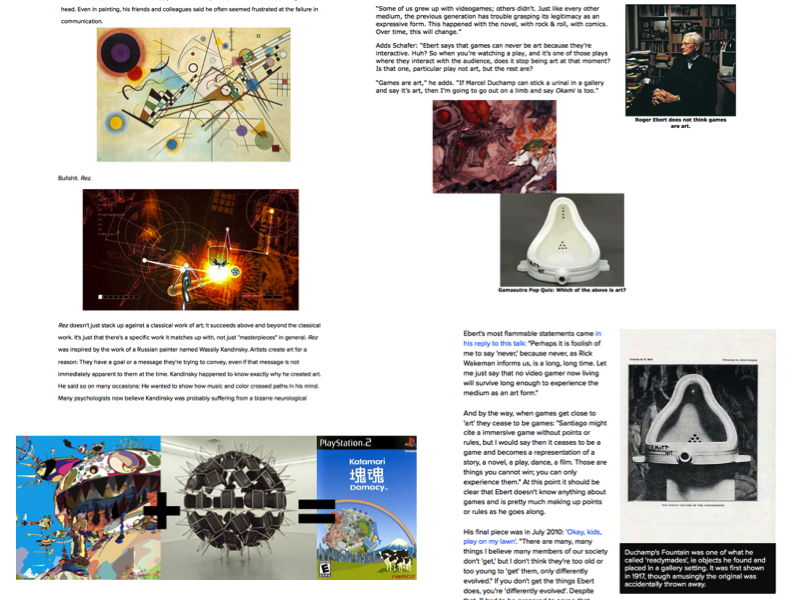

In the following years, a movement of amateur art criticism emerged within the game industry. Programmers started to Google terms like “aesthetics”, game journalists filled their counter-articles with pictures of Duchamp’s Fountain. Because if everything can be art, why not games?

Every strange, intimate, weird looking game was measured for its potential to defuse Ebert’s argument.

Even hardcore gamers started to cry while playing (and blogged about it) demonstrating they also had feelings. Those little sprites and polygons really mattered to them.

In any case, from that cycle of shame and pride emerged a new sensibility. On one side the gaming community matured and developed higher cultural ambitions. On the other, the masses of non-gamers and the mainstream press became more and more sympathetic to the game form.

This coincided with a series of events that have been framed as “victories” by the industry, like the move by the National Endowement for the Art to accept games as possible recipients for grants.

Although, as few have pointed out, in the past the NEA funded videogame projects through individual artist grants. So it wasn’t really a big deal.

Another landmark was last year’s exhibition “The Art of Videogames” at the Smithsonian Museum. Game people were too busy celebrating this recognition to wonder whether or not this was a just populist publicity stunt to refresh the museum’s image and the industry’s. The show was in fact “generously” supported by Entertainment Software Association.

The curatorial process was also populist and designed for buzz. It involved an online poll asking people to vote for the games to be included in the exhibition. Of course fans love to argue about lists and top tens. But it didn’t make a big difference anyway, because only 5 among the 80 chosen titles were actually playable in the exhibition.

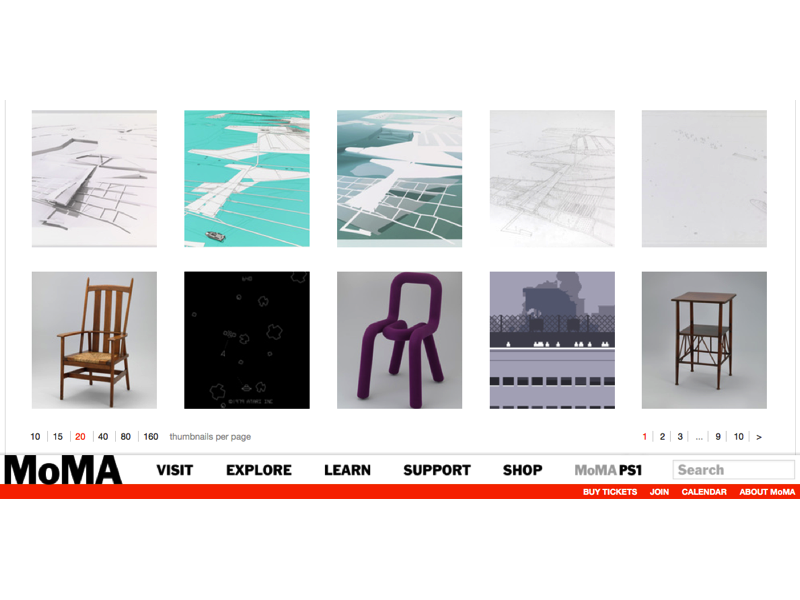

The ultimate institutional validation was the inclusion of 14 games in the MoMa’s permanent collection. Here too we were so busy celebrating that I haven’t heard many commentators reflecting on the fact that the acquisitions were part of the Architecture and Design collection, and not the art.

What does it mean to put Asteroids right next to swanky furniture and unrealized architectural proposals?

Is the hip and yuppie field of interaction design imperialistically claiming videogames?

Are games furniture?

Can architecture make you cry? (like videogames)

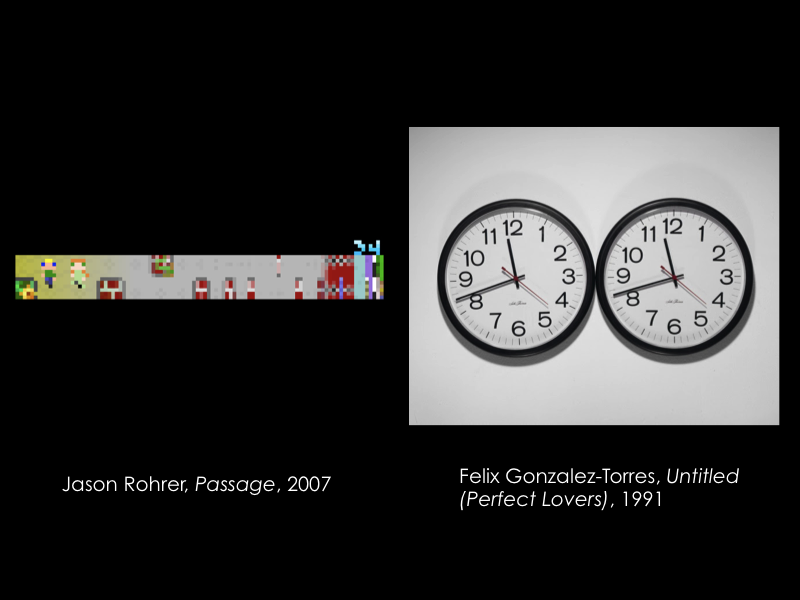

For example I’d like, one day, to see the art game Passage exhibited next to Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Perfect lovers”. If you don’t know Gonzalez-Torres’ piece, it’s super simple: two identical clocks are set in unison but over time they will inevitably fall out of sync with one another.

Both works explore themes or time and eternal love; they are tragic and romantic; they are biographical (Gonzales-Torres made this after his partner was diagnosed with AIDS. Passage has a similar background story).

And now they are both part of the MoMa collection. Except that Passage is in the design department. Will these worlds ever collide?

But the most important thing that was missing from this long Games as Art debate was the acknowledgment that artists have been working with videogames for almost 20 years now.

Videogames have been a constant fixture in digital art festivals and exhibitions around the world. There have been a multitude of specifically game-themed exhibitions in the last 10 years.

And the reason why this trend remained under the radar of the game community and of the mainstream press is because it could not be summarized with a simple “Whaaat? Pac-man in a museum?” headline. Because the lines of engagement between art videogames are rich and complex.

I want to give a brief overview of these different approaches. This is not meant to be a taxonomy made of neat boxes, but more like a glitched up collection of intersecting planes.

(Disclaimer: I will not mention my own stuff, I’m not that kind of person)

So when we talk about games and art we should think of many things:

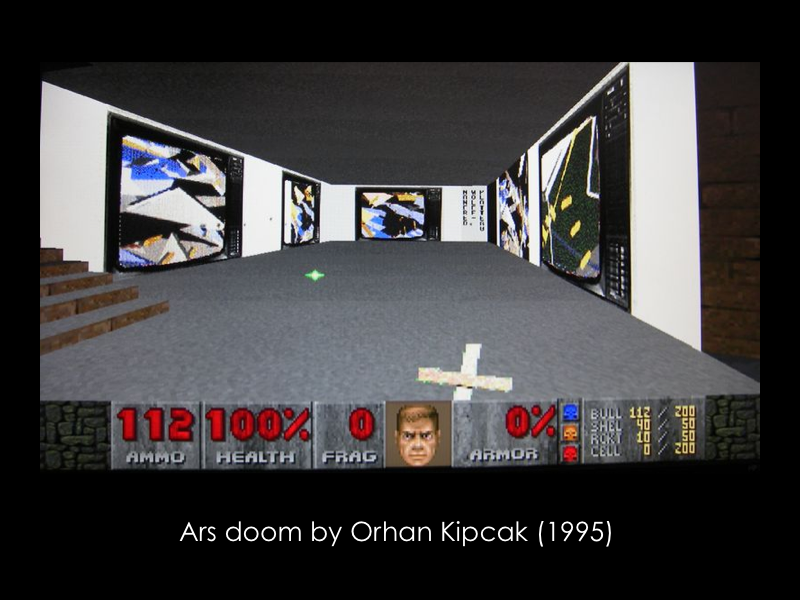

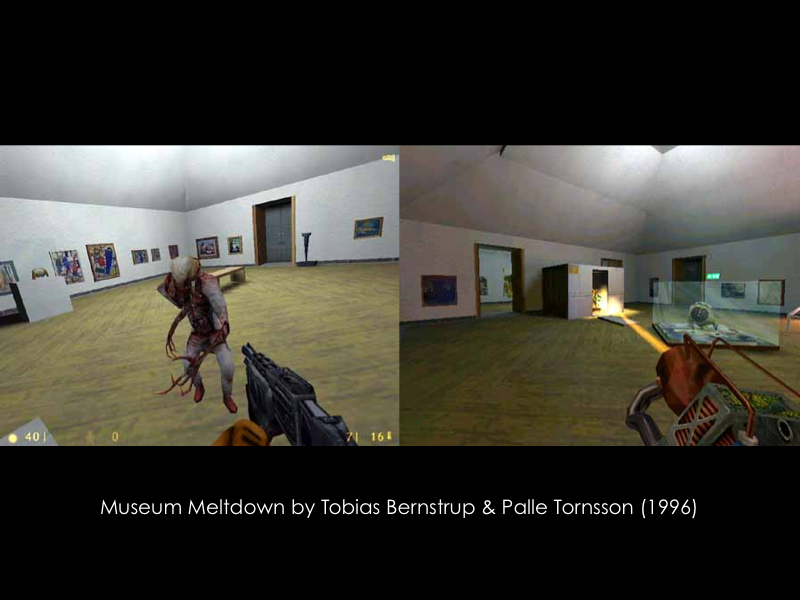

Art mods

One of the earliest strategies was the art mod. I’m referring to artist that use or appropriate game technologies to create interactive screen-based pieces.

For example to create twisted virtual museums spaces within real museums.

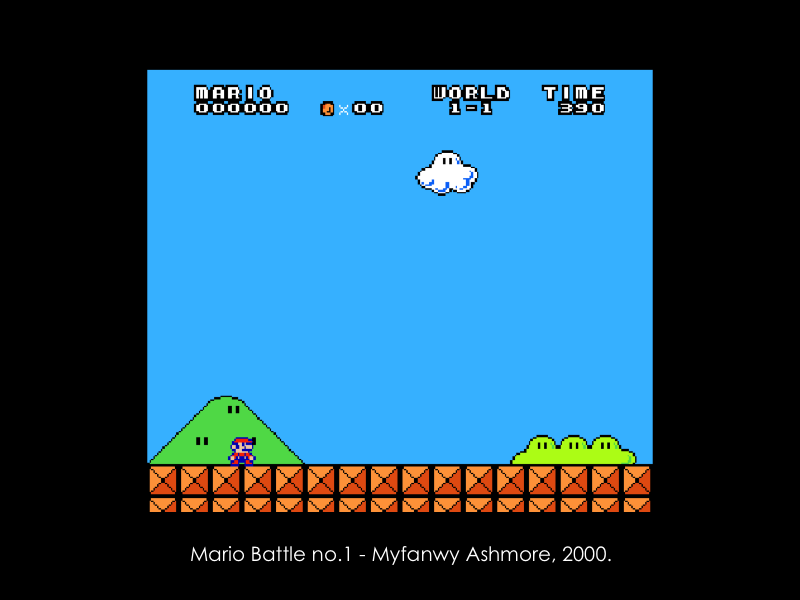

Or removing elements to create new meanings and experiences. This is a mod of Mario Bros from 2000 with all the enemies removed. This work is where Cory Arcangel got the inspiration for his famous “clouds”.

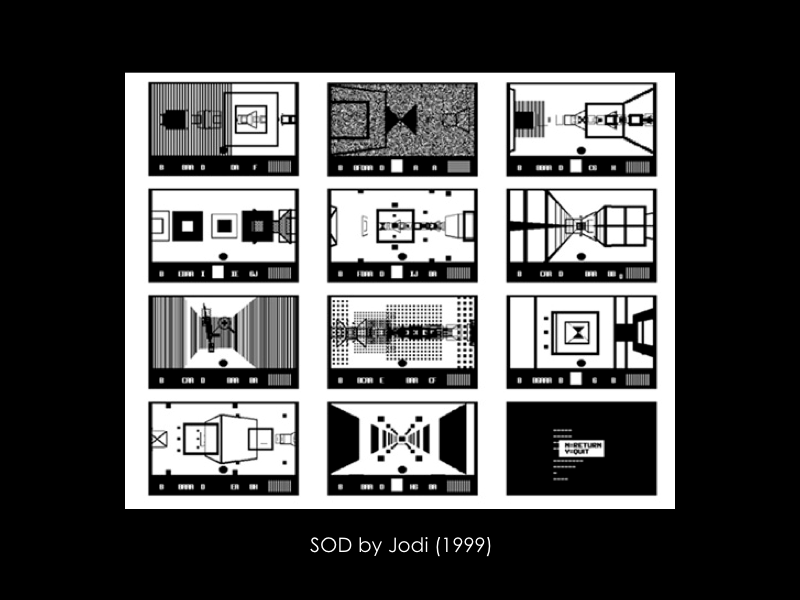

Or the radical interventions on first person shooters by Jodi. Changing the texture of Wolfenstein 3D and turning it into a kind of constructivist painting. This is actually playable and it’s quite enjoyable.

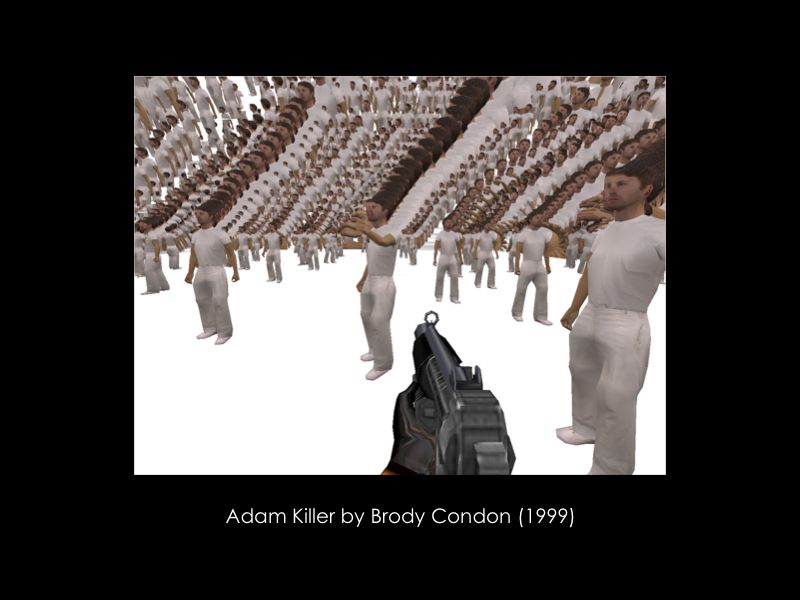

Or the early work by Brody Condon. Amplifying the violence of a FPS when everybody was freaking out about game violence and Columbine.

Or the early work by Julian Oliver: turning Quake into a performance environment or into a generative audio visual artwork performed by bots.

I want to show you a couple of videos from my favorite artist working with art mods.

Joan Leandre, aka RetroYou, is a Catalan artist. All of his work is visually and sonically exquisite. It’s a bit of an acquired taste, early Glitch aesthetic. It’s a luddite attack to the polished surface of 3d games.

These artists are almost saying: it took centuries of visual art, and the invention of photography, to finally be able to appreciate abstraction. And yet videogames are going the opposite way, getting more and more realistic. And boring. Fuck that.

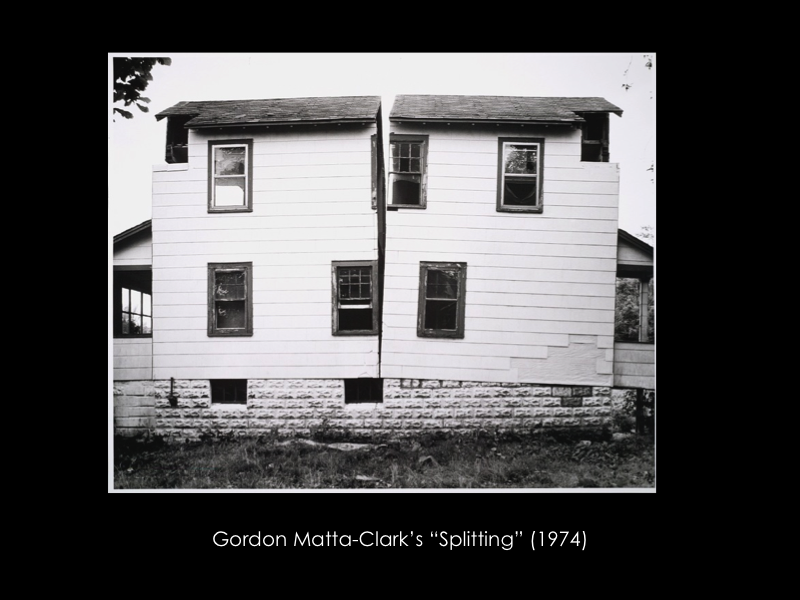

I like to think about it as a Gordon Matta Clark type of intervention: a cut though the surface of an engineered artifact that reveals its inner workings, the digital matter, the guts and the flesh of a game. The invisible bounding boxes, the hidden variables.

It’s not just a fuck design/fuck architecture statement but rather: “let try to see trough these boxes, literally, let’s imagine new affordances”.

Games made by artists

There is this tautological definition of art that reads: “art is what artists do”. Which is not completely useless. It implies that art can’t quite emerge by accident. There is an artist intention, there is identification with a certain role in society. In case of trained artists, there is a degree of literacy at the very basis of artistic practice.

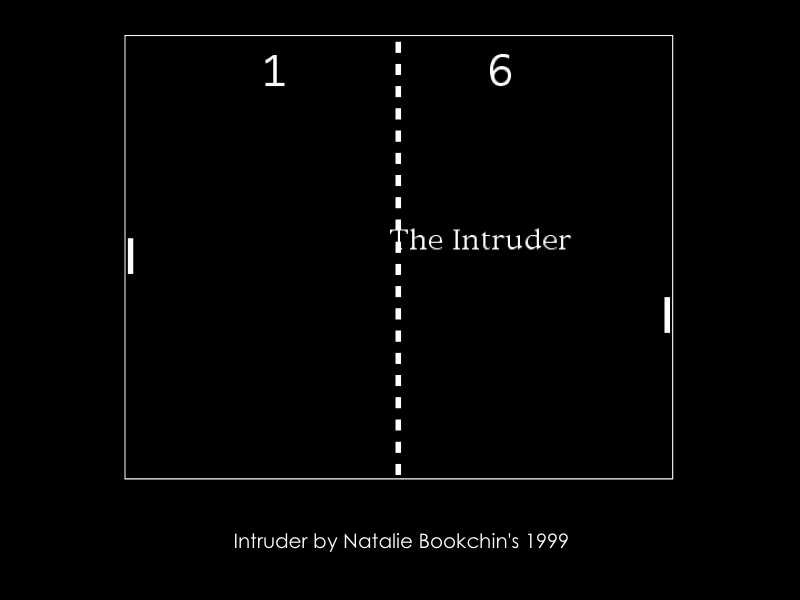

Well known examples include Natalie Bookchin’s The Intruder. A mash up between poetry and classic arcade games.

Or the Night Journey conceived by Bill Viola. Everything made by Bill Viola must be art right? In fact it is so fine art that you may never get to play it, unless you go to a fancy gallery in a fancy city.

This crosspollination happens in the commercial world as well.

Toshio Iwai, the maker of Electroplancton is a Japanese interactive media and installation artist.

Fumito Ueda graduated in art, tried to make a living as a painter, failed and then switched to the game industry.

But his background shines through his work in the AAA game industry. His creation process is very visual, he conceptualized Ico and Shadow of the Colossus through an computer animation instead of a game prototype.

Visual and sensory experience first.

Keita Takahashi studied sculpture, and his object-based sensibility is so evident in both Katamari and Noby Noby Boy.

Games about art

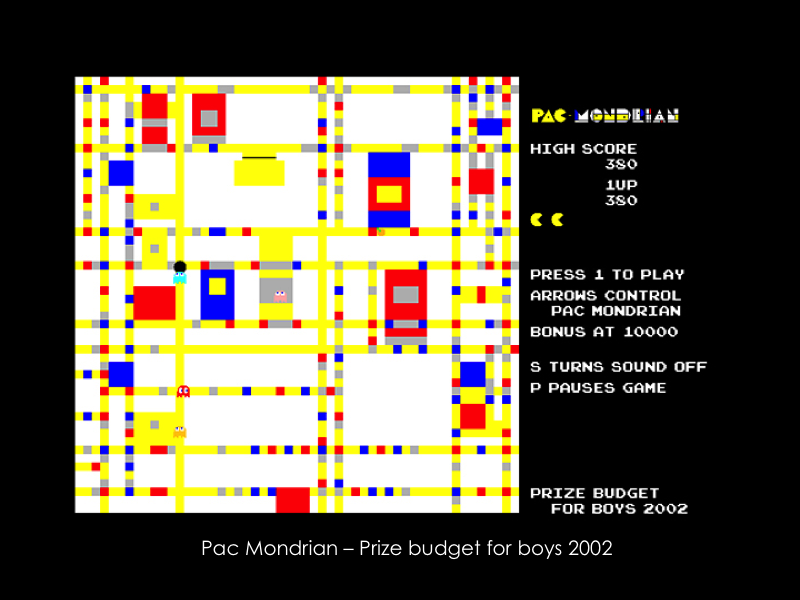

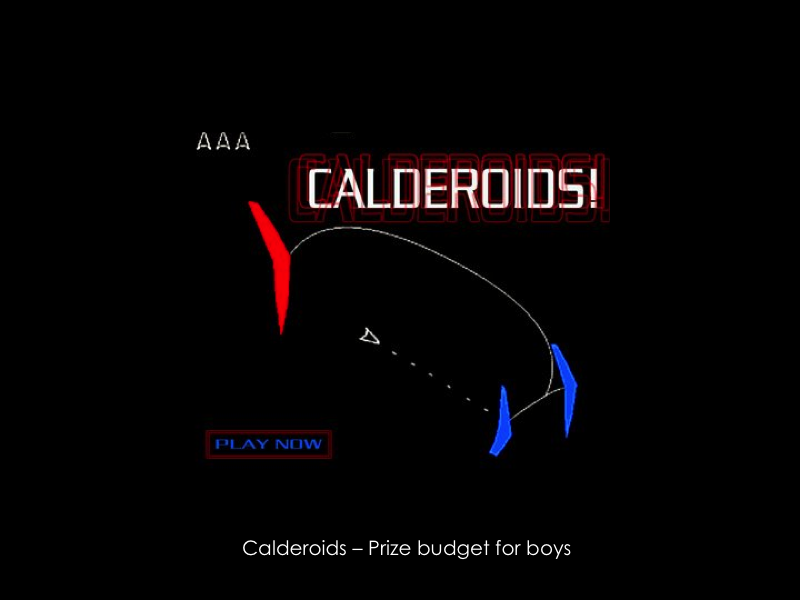

This is another approach or subgenre: games that specifically reference art or are themed after artworks.

This is the most straightforward way to frame your work as art. It’s a classic post-modern trick: hi-brow meets low brow. But it’s a trick that works because the artworld is not that different from any other geek subculture: we have our own culture, our inside jokes, and we love things that makes us feel like we belong to a community.

Of course there is a problem of accessibility. It is hard to understand Pippin Barr’s the Artist is present without being at least aware of Marina Abramovic’s performance of the same name. The game is a simulation of the absurd experience of being there, waiting in line in order to have a staring context with the art star.

Games about art select their audience. I’m personally wary of taking a popular form and “elevate” it to an high culture status, even when it’s through self-conscious humor or parody. But we have to keep in mind that contemporary artists are always in dialog with artists of the past and are always drawing from other cultural fields. There’s a lot of art about art and sometimes it’s more than inside jokes, it’s a sign that art and the art system, much like the scientific consensus, is in constant revision (feminist remakes, institutional critique etc.).

And I think there is a great potential in games that are community and culture specific, as opposed to designed to reach the widest audience possible.

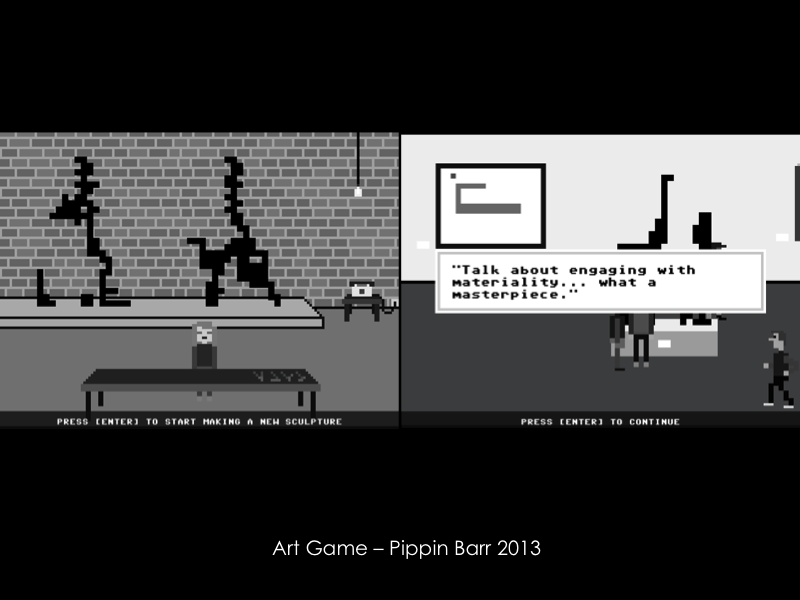

Art Game by Pippin Barr goes a step beyond the art reference and “simulates” the artistic process as a game within a game. Satirizing the plight of the self-absorbed artist, the arbitrariness of value in contemporary art and its abstruse language is quite easy, but the game also draws some interesting parallels. If games are art, what about the detritus of the gameplay? The piles of tetris blocks, the trajectories of space shooters… Maybe the artworks that are not games by themselves are simply the outcomes of playful acts.

Games redefining play

Games redefining play may be an awkward wording but I want to make sure I’m not referring to experimental games – as in games-with-novel-gameplays. With the rise of independent development, innovation is becoming the norm. The game language is evolving faster now than ten-fifteen years ago, when only the technological advancement seemed to dictate the game forms, but being original is not the unique prerogative of artists.

Here I’m talking about works that are presented as games but are intentionally pushing the boundaries of gaming.

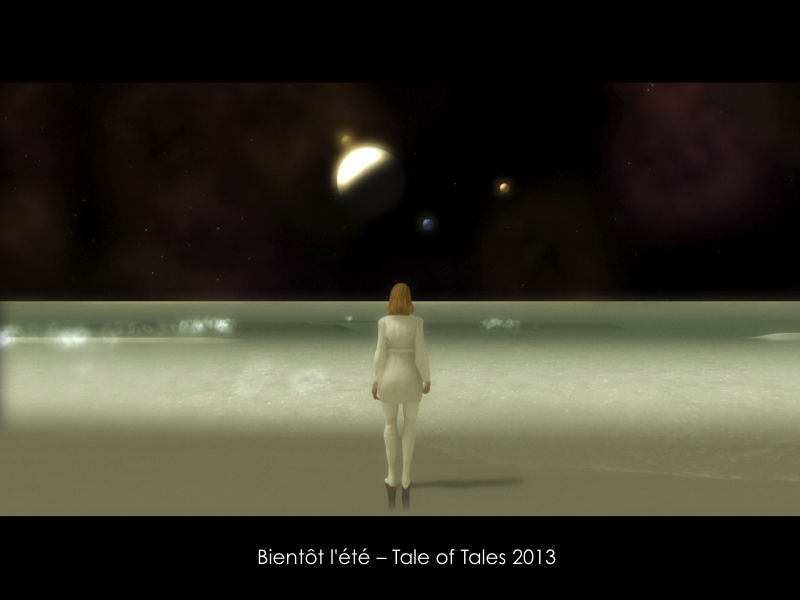

This is the case of the so called NotGames by Tale of Tales, among the others. These are works that use game technology and game conventions but intentionally deter a goal-oriented mode of play.

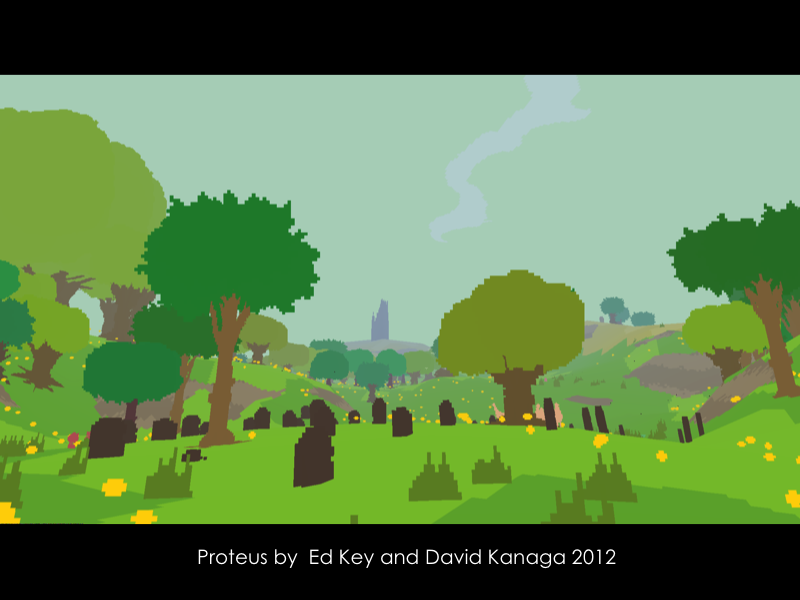

The synesthetic exploration game Proteus gives the player a very limited agency, an agency that has nothing to do with the control over the environment. Rather, it lets you modulate the experience of its rich hyper-natural soundscape.

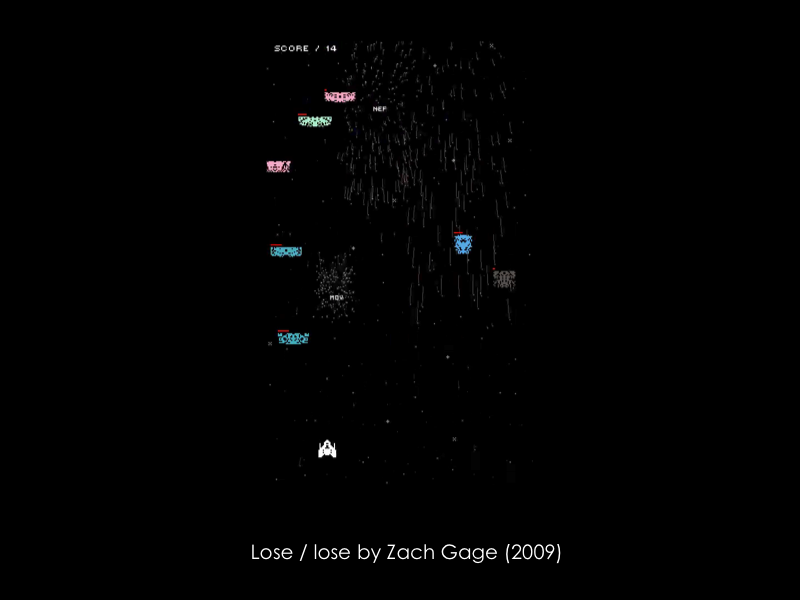

Aside of goals, this kind of work can challenge other aspects we tend to consider core properties of games. For example the safety of the cybernetic magic circle is violated by Lose/Lose a game that deletes a file from your computer every time you defeat an enemy.

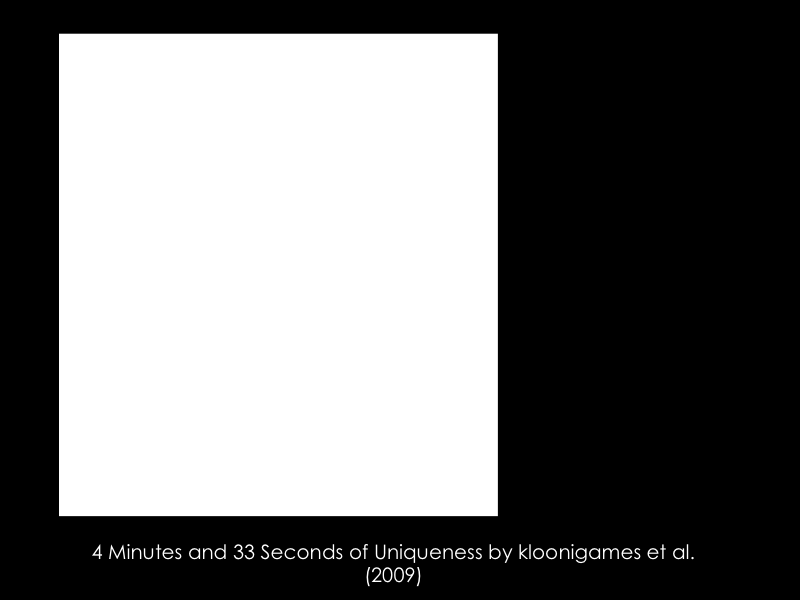

Or challenging the idea that winning a game is a matter of skill or chance. This game, referencing John Cage has almost no visuals, only a loading bar. It’s an online game that you play by simply running the file and doing nothing. The goal is to be the only person in the world who plays it for 4 minutes and 33 seconds. If somebody else in the world runs it, you lose.

Vesper 5 is another game that literally stretches the experience of play to the extreme. The goal is to explore the area and reach a point in the map, but you can only take one step per day (real life day). The act of playing becomes a ritual that requires a unusual type of commitment and patience.

Game Art

This is the most “conservative” line of engagement between art and games. By game art I mean artworks that do not employ a game medium but incorporate motifs or themes that belong to game culture.

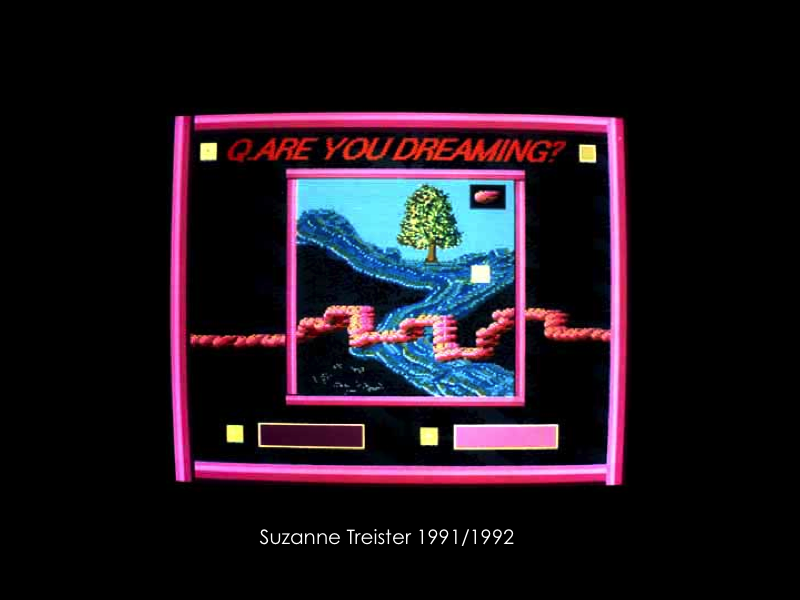

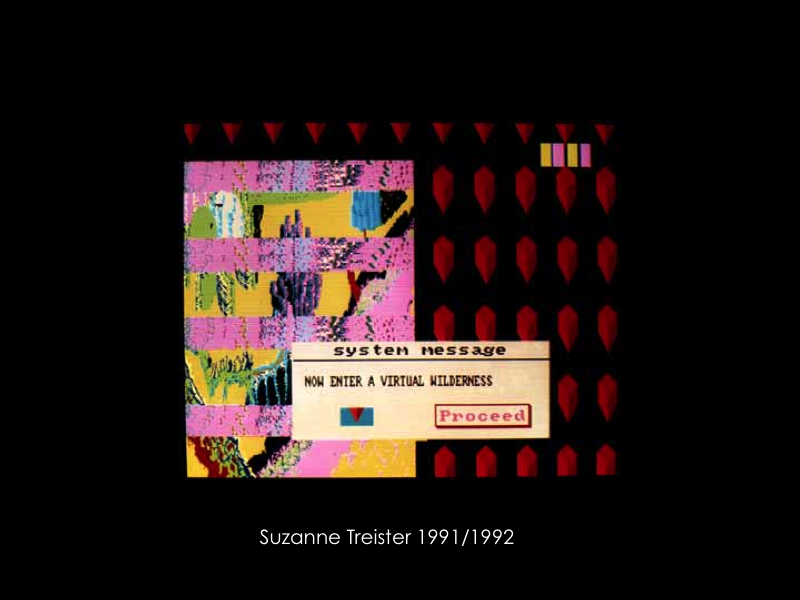

One of the earliest examples I could find is this series of imaginary game screenshots from the early ’90. They look like contemporary weird indie games but they are just digital images made by a visual artist.

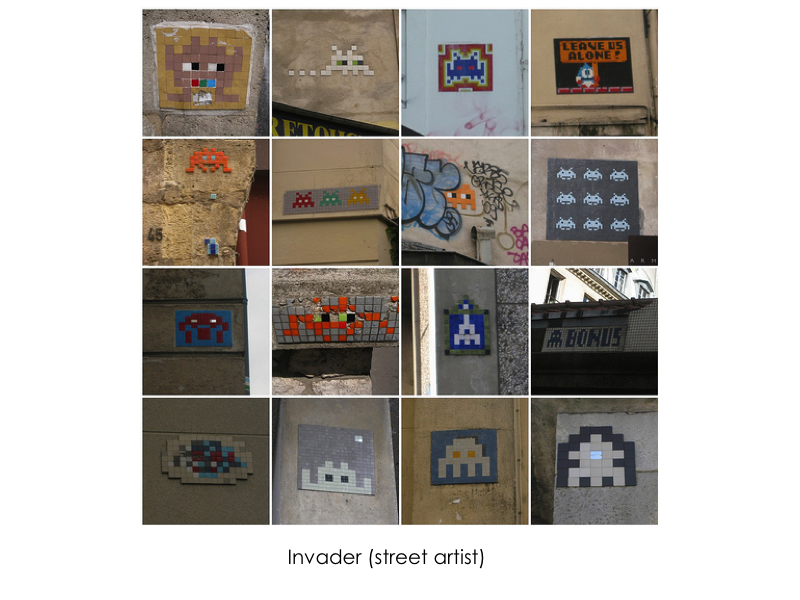

Some game art follows the tradition of pop art.

Referencing commercial culture and giving it a fine art treatment. Sometimes these works are indistinguishable from glorified examples of fan culture.

But some game art can produce powerful images or objects that can give us insights on our medium and community. Is the Modern Fossils series a commentary on planned obsolescence in gaming?

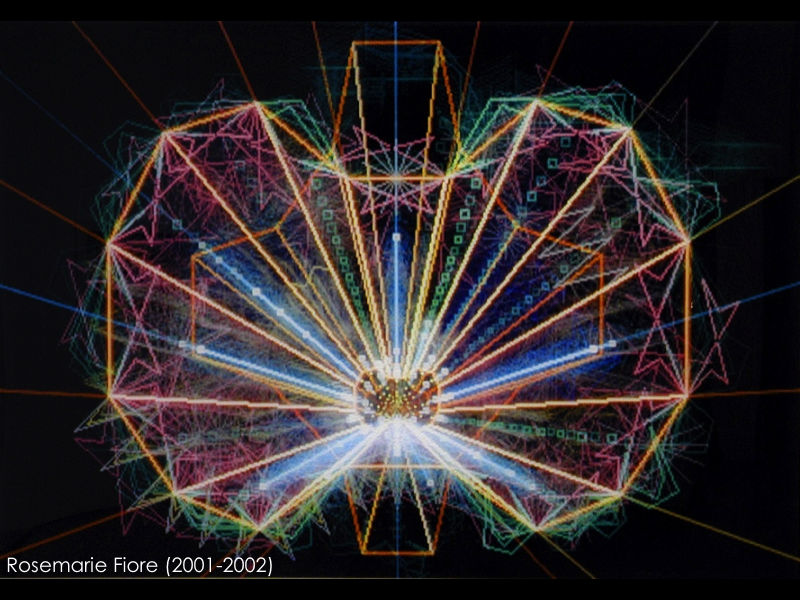

This series of long exposure screenshots by Rosemarie Fiore are striking portraits of gameplay patterns.

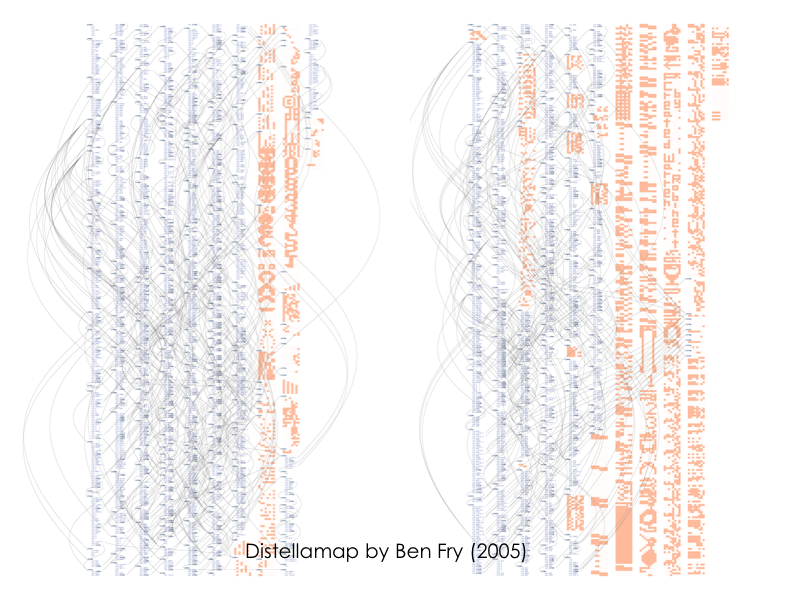

Distellamap is a series of infographics that unpack the source code behind classic Atari games along with their execution flow.

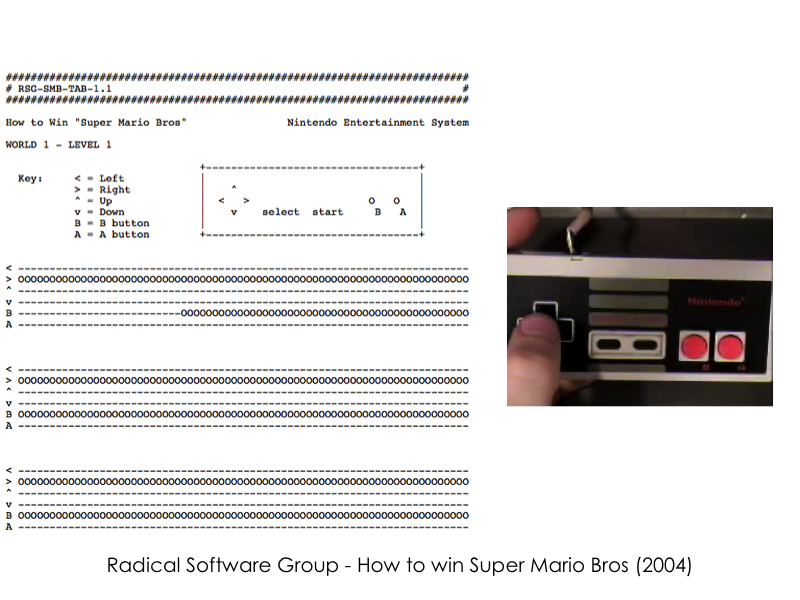

Or this project from the player perspective. It’s a tab, like a guitar notation, that contains a perfect playthrough of Super Mario.

It makes you wonder if there is a space for creative play in that kind of game. Is the act of playing just an exercise in muscle memory?

And yes, these works are not games, but ignoring them on the basis of the artistic medium, puts us out of touch with contemporary artistic practice. Contemporary art has been steadily moving away from a medium-based approach toward a post-media practice.

Artists don’t want to be confined into ghettos like video art, installation art, new media art. They want to be able to adopt different media according to their needs.

Art with games

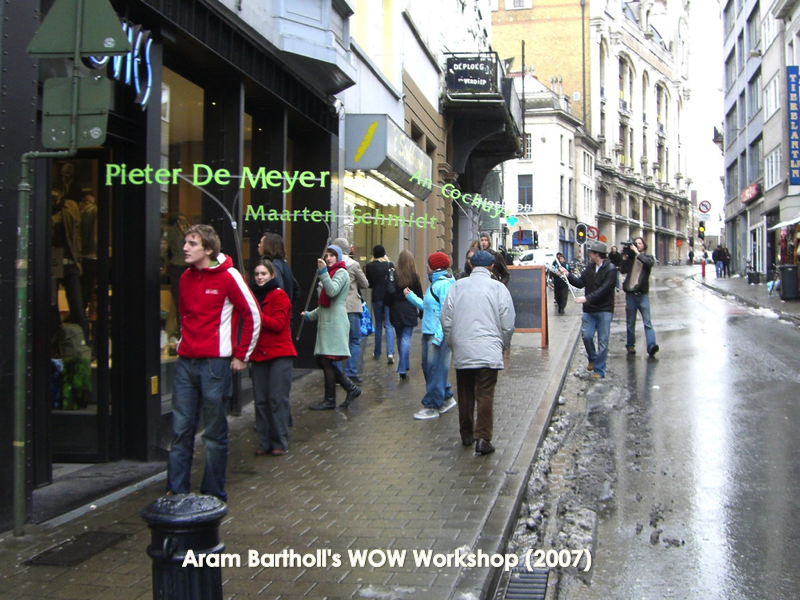

There are practices that tackle games from a performative angle.

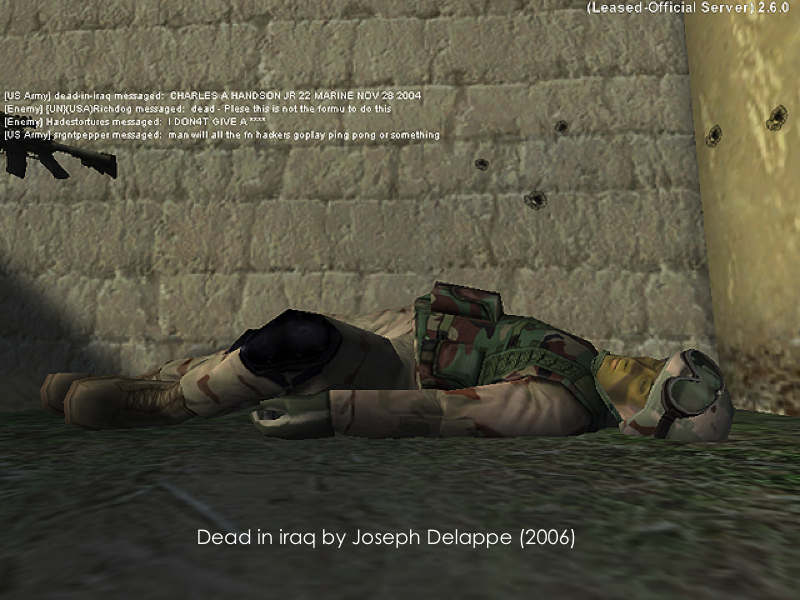

Dead in Iraq is a digital performance and a memorial to the fallen soldier in Iraq that takes place inside American Army’s servers. The artists logs in the well known recruiting game and every time his avatar dies he types name, rank, and date of death of an actual soldier, short-circuiting the reality of war with the propagandistic depiction of the first person shooter.

Machinima can also fit in this genre. People tend to associate machinima with fan-culture or with that lousy comedy series set in Halo, but artist have been doing great machinima even before that term was coined.

For example this is a systematic study on game deaths by Brody Condon.

This approach doesn’t really relate to the question: can games (as objects) be art but rather: can games be played or misplayed artfully? Can players be artists?

Of course we have a lot of games like Minecraft or Little Big Planet that enable players to be creative, which is an euphemism for generating content for free. But it’s a Lego set kind of creativity, that smells like STEM informal learning.

Art performances within games are typically antagonistic to the products they use. They are exploits, conceptual hacks that expose certain technical or ideological limits of commercial games.

But I wonder if antagonism a requisite for meaningful intervention.

Is it even possible to create game artifacts that embrace and encourage this kind of expressive, critical and subversive play?

Artgames

The artgame genre or movement emerged mostly within and around the game industry. Artgames don’t try to break all the rules of gaming. They don’t try to challenge our idea of game. Rather, they put a strong emphasis on craft and on the procedural aspect of videogames. It’s art as in “art rock”, as Jason Rohrer once put it.

The gameplay, the formal system of rules, is the primary vector of expression. And the narrative component is tightly coupled with it.

Themes too, tend to be different than the ones found in traditional videogames (so far at least).

Games for grown-ups

This takes me to another plane that intersects most of the others: games for grown-ups. They are a reaction to an industry dominated by teenage fantasies.

The issue of content comes up frequently in the discourse around art and games (please enjoy yet another fanboy headline). You have titles like Bioshock that kinda give you the impression of dealing with important themes while you are shooting and blowing things up.

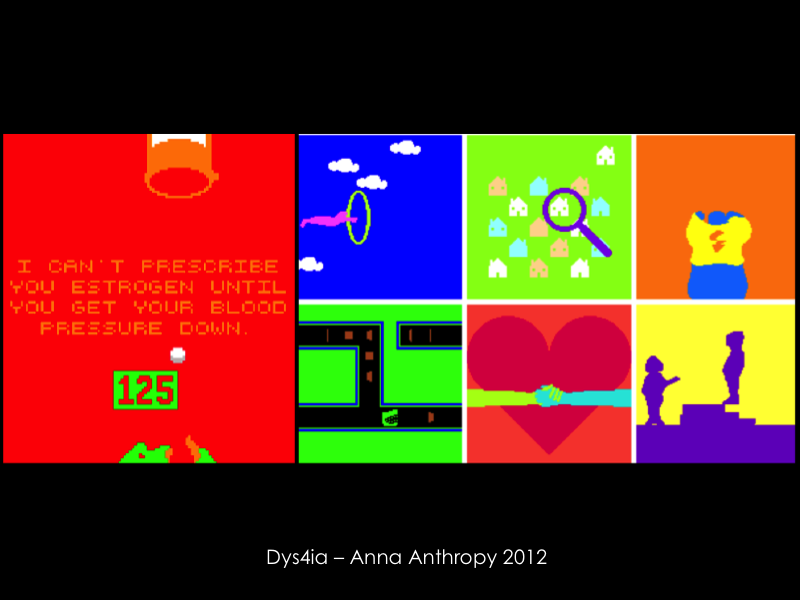

Or works that aim to solicit a range of emotions that are not typically associated with games and competition.

In this idea of games (and gamers) growing up there is a hierarchy of emotions. Some feelings seem to be more adult and noble than others: empathy, melancholia, nostalgia. A work that moves you is for some reason more highly regarded than a work that makes you laugh or freaks you out.

There is a well known trope in videogame culture: Can video games make you cry?

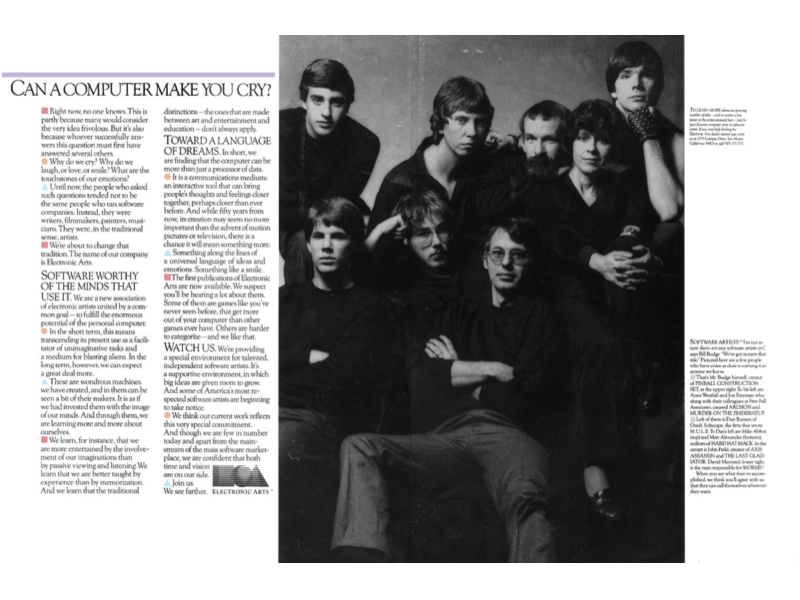

It originated from this Electronic Arts ad from 1983.

It’s a really nicely written manifesto – and a cool rockstar photoshoot. It’s so hard to believe that it was the origin of what is now one of the most conservative game companies in the world. A cautionary tale for all young indies.

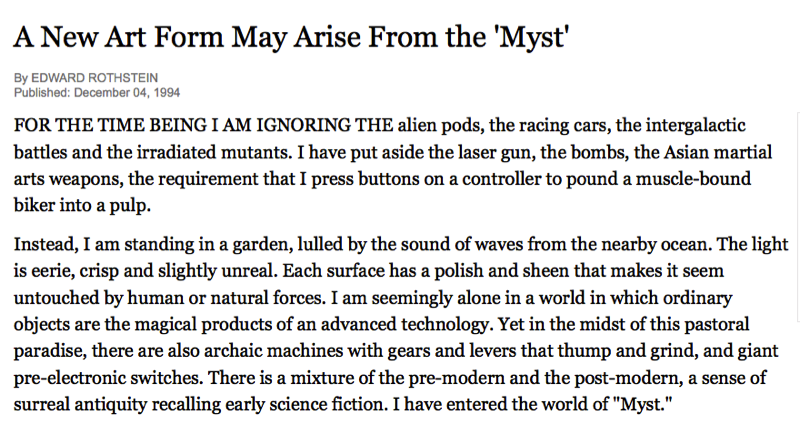

The trope of noble emotions re-emerged in the mid ’90s when Myst came out and was saluted as the first example of artistic game. Almost 20 years later this opening paragraph can be applied to a bunch of recent titles I mentioned before: Dear Esther, Bientot L’ete, Proteus, the Witness…

Let’s be clear, I’m glad to see games exploring and soliciting different responses. But I also think it’s time to abandon this hierarchy of emotions in relation to the artistic merit of a game.

Most contemporary artist couldn’t care less about making people cry, that’s the job of cheesy Hollywood movies or drama TV shows. And many artists working with games and game culture are actually very much into violence.

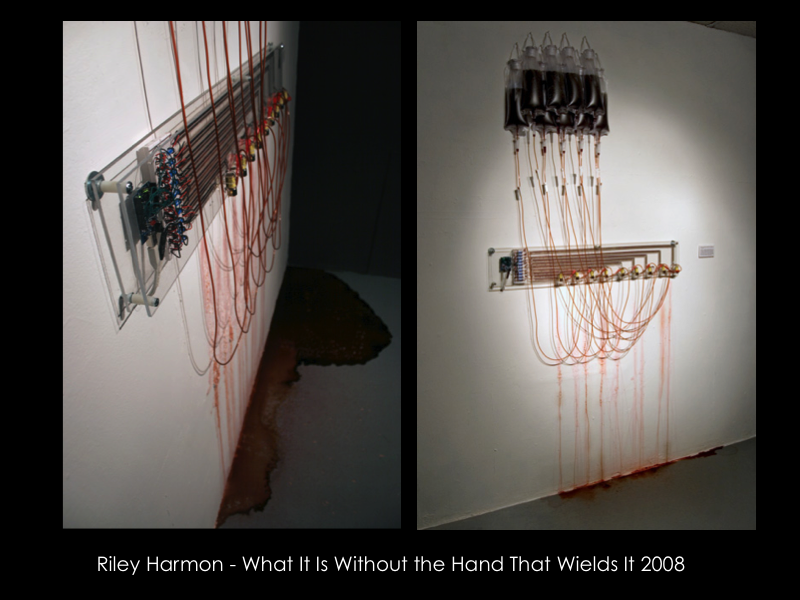

A sculpture connected to a Counterstrike Server that spills a drop of fake blood every time somebody dies online. Or the isometric screenshots I showed before. Or the work by Eddo Stern which I’ll show in a second.

That’s because these artist’s interest is in games as a techno-cultural phenomenon. They are trying to explore how these games are products of a specific society, in a specific moment in time.

When digital artists, decide to adopt a game form it is often because they are interested in investigating the nature of medium itself, and not just use it as a device to express or manipulate emotions.

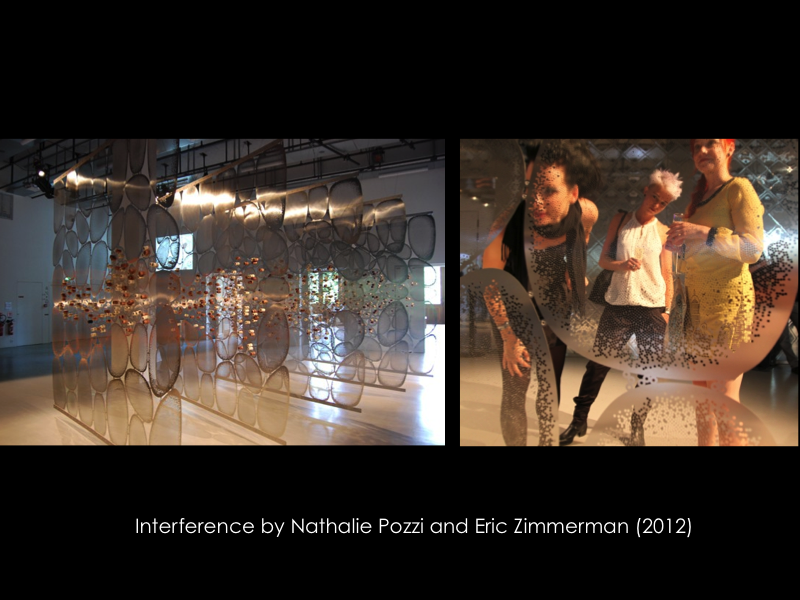

Installation games

Some games are specifically designed for art spaces and art audiences.

Painstation is a good early example one. It’s a Pong clone that introduces real pain in the competition: your hands get electric shocks, burns, and lashes every time you miss the ball. You lose when you can’t stand the pain anymore. It’s a very intense experience.

Eddo Stern’s Tekken Torture Tournament (from the same year) is also connecting virtual pain with physical pain, and is presented as a fight-club like event.

I find fascinating that both these work and several others in this genre satirize the macho posturing of many mainstream games. They over-identify with them and make violence appear even more over the top.

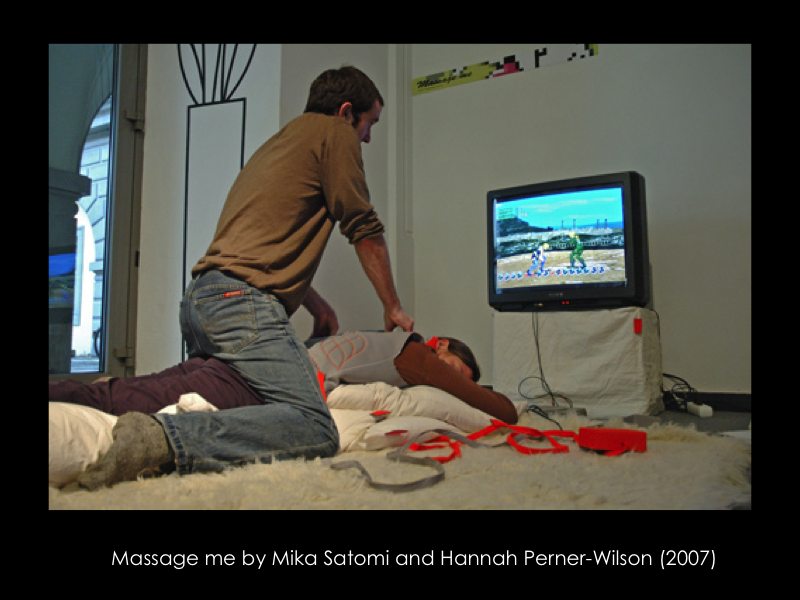

Some artists (perhaps not coincidentally women) took the opposite approach when transforming game interfaces for art spaces.

In Sweetpads you play a Quake deathmatch by gently touching a sphere. If you are too rough the game doesn’t respond. This is also an intense experience. Imagine seeing your rocket launcher-wielding enemy slowly turning toward you. You can’t panic or twitch react, only softly caressing the controller hoping to have enough time and focus to evade.

By simply enlarging the controller, Mary Flanagan turned single player Atari games into collaborative experiences, since moving and firing requires the collaboration of multiple people.

In Massage Me a wearable game controller converts button mashing and combos in Tekken into a massage for the benefit of a non player. The gamepad/corset is cleverly designed to allow both meaningful controls and pleasurable massage patterns.

Installation games bring up the issue of art spaces. Art is not only what artists do but also whatever lives (or dies) in a museum or a gallery. Like it or not, the job of most artist boils down to fill some empty space, to take advantage of, and justify the existence of the art infrastructure:

These white clean rooms, where civil and educated people hang out. I’m personally not interested in creating work for these institutions, because I’m not interested in entertaining the mainly privileged people who hang out in these spaces.

And I believe the most interesting art now happens outside of the white cube: net art, social practice, creative activism, performance.

These practices are rarely mentioned in the Art vs Games discourse because we are obsessed by museums, and yet they have a lot of things in common with games and play.

But I also believe these traditional art spaces are interesting and important because they have unique affordances: they allow you to have a complete control of the environment and the players. You can do illegal stuff, you can do very unpractical stuff, you can do grandiose and insane stuff without fretting about game systems or distribution platforms.

This is very different from the museification process that got gamers and industry so excited.

When I look at this artsy MoMafication of Pac-Man: grey, dry, walltexted, with headphones, I start to think that maybe Pac-Man doesn’t need to be there in that space. Maybe the importance of Pac-Man is self evident. And maybe the role of the art system is not to validate already successful commercial works but to enable the existence of works that could not exist anywhere else.

Another question worth asking is: should games with artistic ambitions be more exhibition friendly? Should they be short, easy to learn, arcadey to deal with the short attention span of art consumers?

Games may need to disrupt the exhibitions space. Like performances and time-based art had to before them. In the early nineties black boxes were created to accommodate video art, for example. Festivals and events can be the best ways to bring together performance or socially engaged artists.

We may need to bring some couches, snacks and drinks in the museum. Because you just can’t play Cart Life in 5 minutes while standing.

In conclusion, here’s the problem: all these approaches and questions I just posed did not matter in the games vs art debate. Because that exciting, pedantic, fractal, never-ending dispute we call “art” was never the point of this debate.

The point was to Upgrade the cultural status of videogames as a whole: as a medium and as an industry.

For gamers it was a retroactive validation of the countless hours spent moving pixels around.

For the game industry it was a chance to snort some of that fancy art dust without accepting the responsibilities that come along with working in that special area of culture.

And critics, game makers, and scholars like us, people in this room who know about art and know about games, failed to propose a different narrative, a narrative that highlights the richness and the variety I just outlined.

I don’t have a note for this keynote, but I do have a proposal, a desperate plea:

Let’s stop identifying with the game industry.

Let’s stop being academic/fans and glorify consumer products that were never meant to be more than consumer products.

Instead of being advocates for the medium as a whole we can be advocates for good games and good art.

Because we cannot have an art history of games without an art criticism of games.